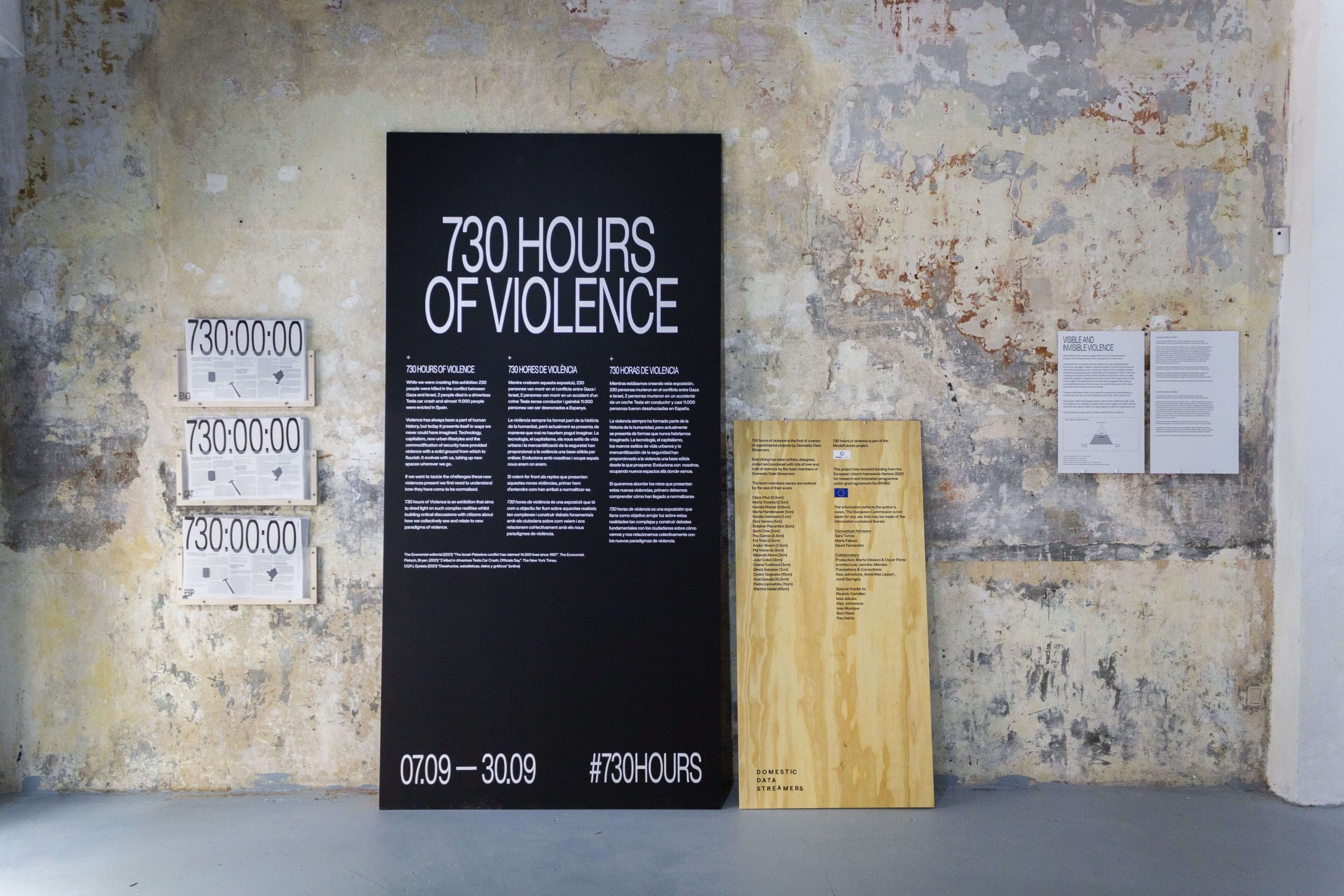

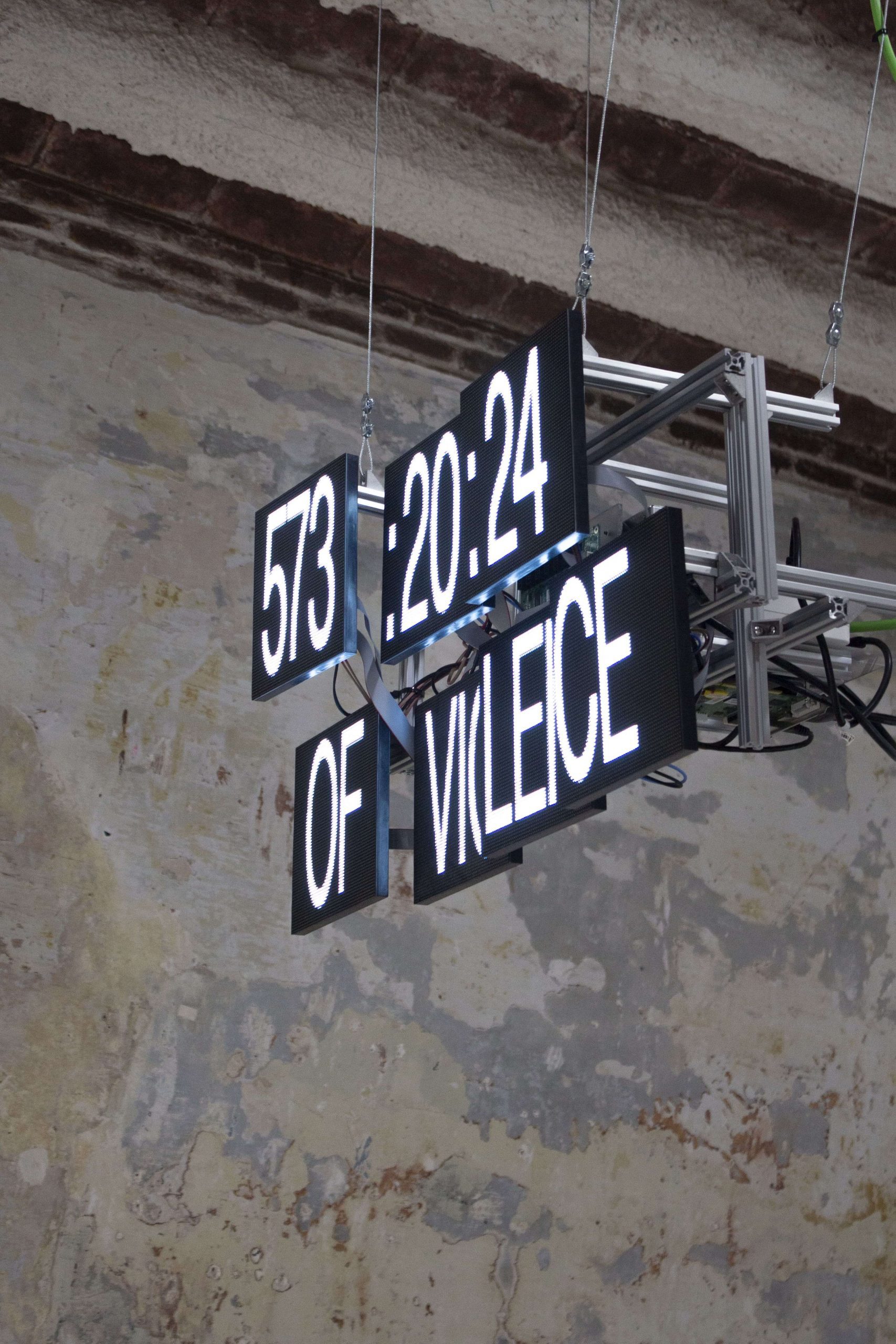

The exhibition is presided over by a counter that marks the hours that remain until the exhibition ends. The project will end when the clock, which started at 730 hours, reaches 0.

The exhibition begins in a room that welcomes the visitor and symbolizes violence as it is usually understood: bombs, weapons and blood stain the visual imagery of what is understood as violence. More often than not, the definitions of the term speak of punches, bruises and interpersonal conflicts.

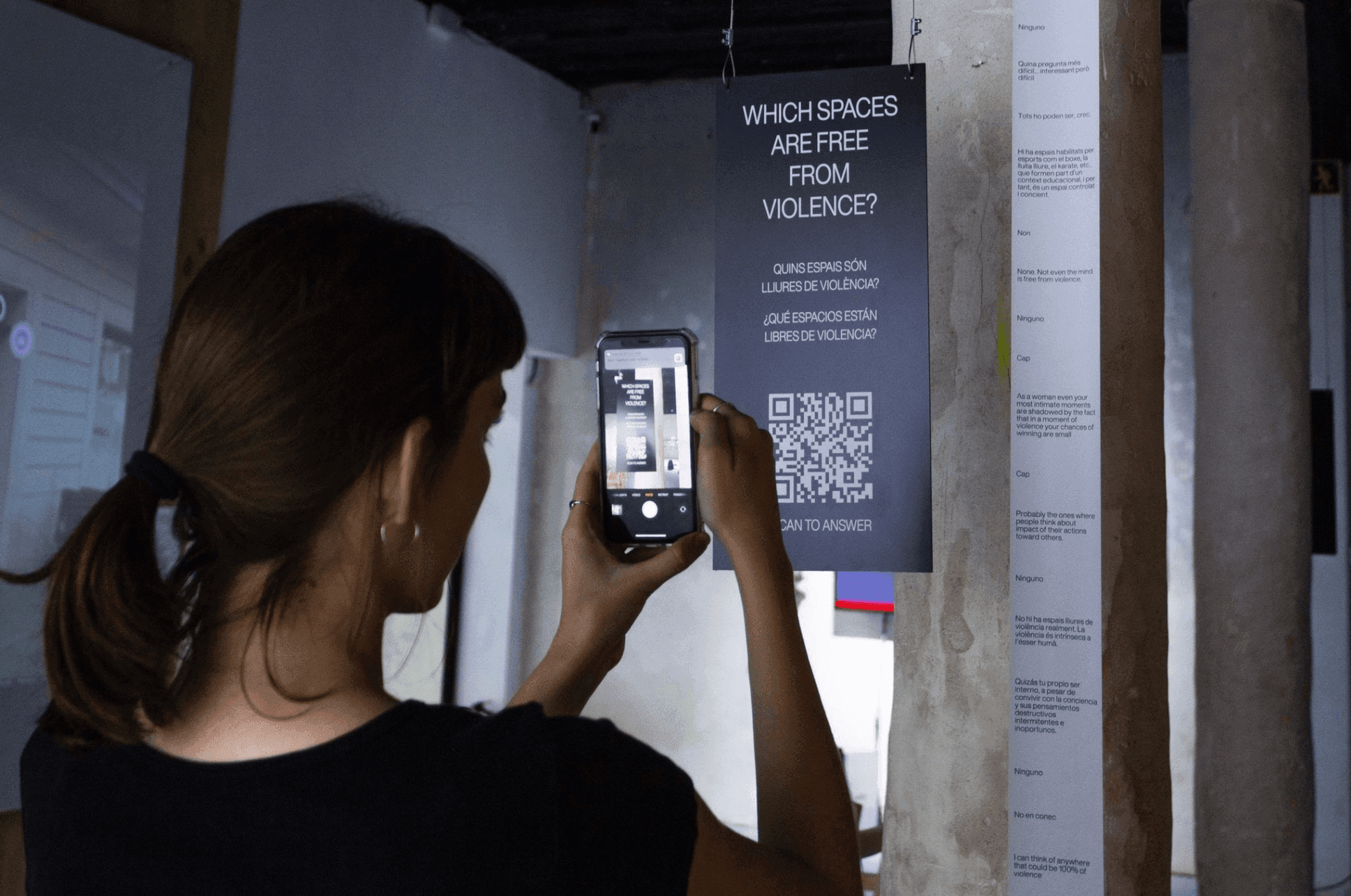

The first piece in the exhibition stems from this context and raises interesting questions: Who has to define what violence is? What does violence look like today? The proposal invites the public to define "violence" using a representative image of the idea, thus generating a collective collage of violence created from hundreds of interactions printed in this loop machine.

To the left of the room there is talk of the first violence "Slow Violence", which occurs gradually and in the shadows, since it is integrated into environmental catastrophes that develop slowly due to periods of pollution or climate change. The concept, developed by Rob Nixon, is visually represented with the autopsy of a fatberg, the "wet-wipe monster" that is generated in the sewers of large cities from the saponification of household waste such as grease, oil, wipes or condoms. The consequences are impressive: the famous fatberg in Whitechapel (London) weighed 130 tons and measured 250 meters.

100 jars anchored to the wall and a video-tour of the sewers of the city of London invite us to recognize the elements that make up this phenomenon and to stop thinking of “slow violence” as an abject concept that has little to do with our individual actions.

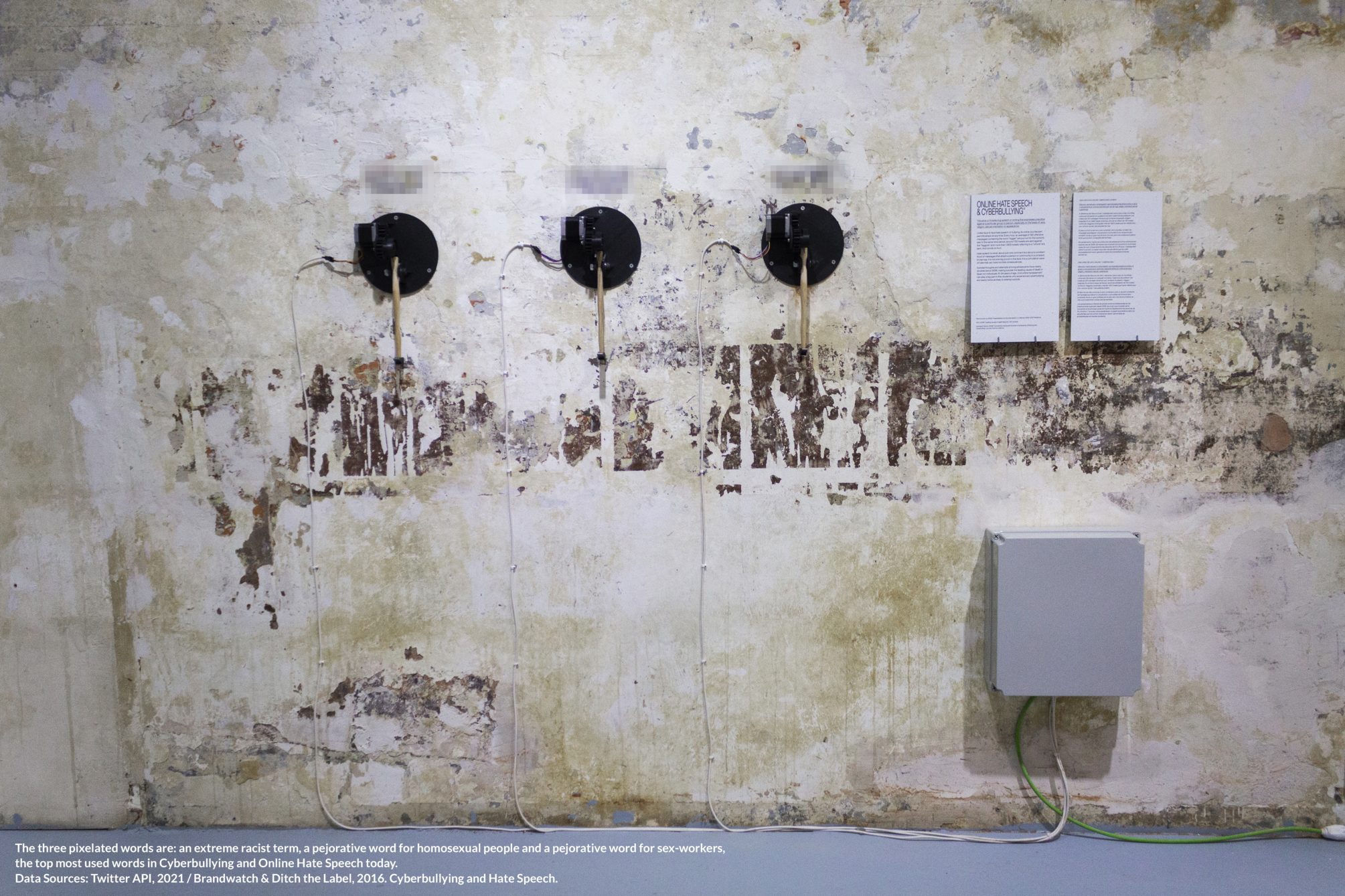

To the right of the room, the second violence: three hammers that wear down the gallery wall. Each at a different pace, marking the surface every time someone in the world sends a tweet related to hate speech or cyberbullying. In this piece, digital action has a real-time impact on the physical world. Specifically, each hammer is assigned a different word: W***e, N***r, and F****t, the three most common words used in online hate speech.

In the centre of the room, we observe the third violence: “Glass Frontiers”, the invisible glass borders that prevent people from exercising their basic rights and freedoms within a city. Four panes of glass that protrude from a mountain of sand mark four different borders that today separate the city of Barcelona: economic, educational, housing and health inequalities. An example of this violence: In L.A. the mortality excess is 23% higher in black and latino neighbourhoods than in other parts of the city. The reason? The scarcity of trees in that area. The lack of public investment translates to less trees which have a big impact on the health condition of L.A. citizens.

The following work is on Data violence, a term that opens a debate on the biases that programmers leave in algorithms and their consequences. The piece uses security cameras and an algorithm that classifies the visitors of the exhibition. In this way, the audience will be judged randomly by an algorithm. A criticism of the apparent objectivity, the margin of error and the power that numbers have in deciding a person’s future.

Selfie dysmorphia speaks of another type of violence. That of the body image disorder that reflects the need to largely edit the digital image itself. 21% of young people feel bad about themselves after looking at social networks. The work addresses the self-exerted violence that is linked to the immense unhappiness we feel with our appearance after using digital filters. The piece facilitates a journey through 6 filters where the public interacts with two versions of oneself: the perfectly instagrammable, and the brutally honest.

The tour ends with three sculptures inspired by the intangible violence that we see both in public and intimate spaces.

Five chairs redesigned to be useless speak of the 160 examples of hostile architecture found on the streets of Barcelona. A video tour shows these examples in their original setting. A violence that, once detected, can be seen even through Google Maps.

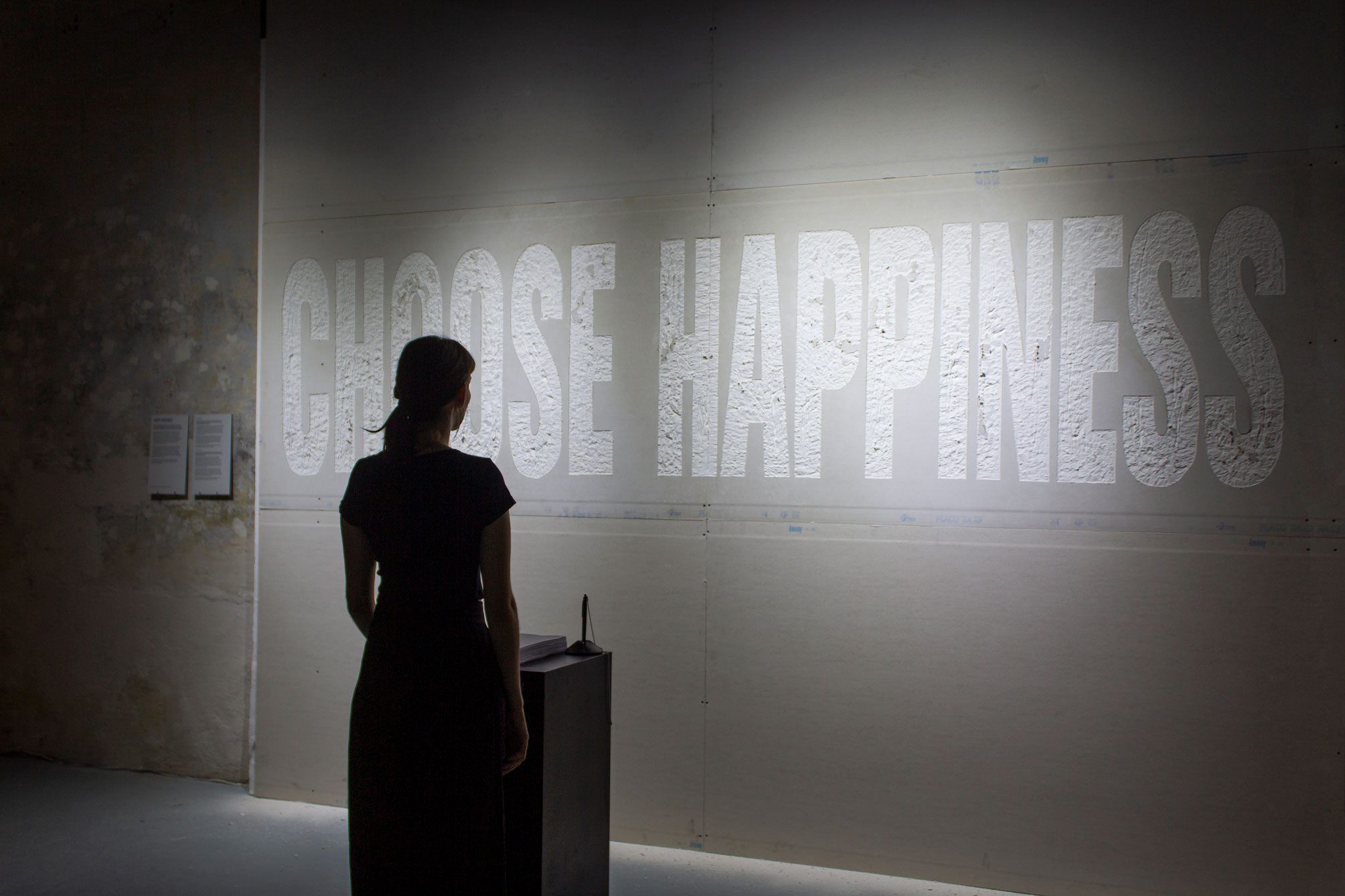

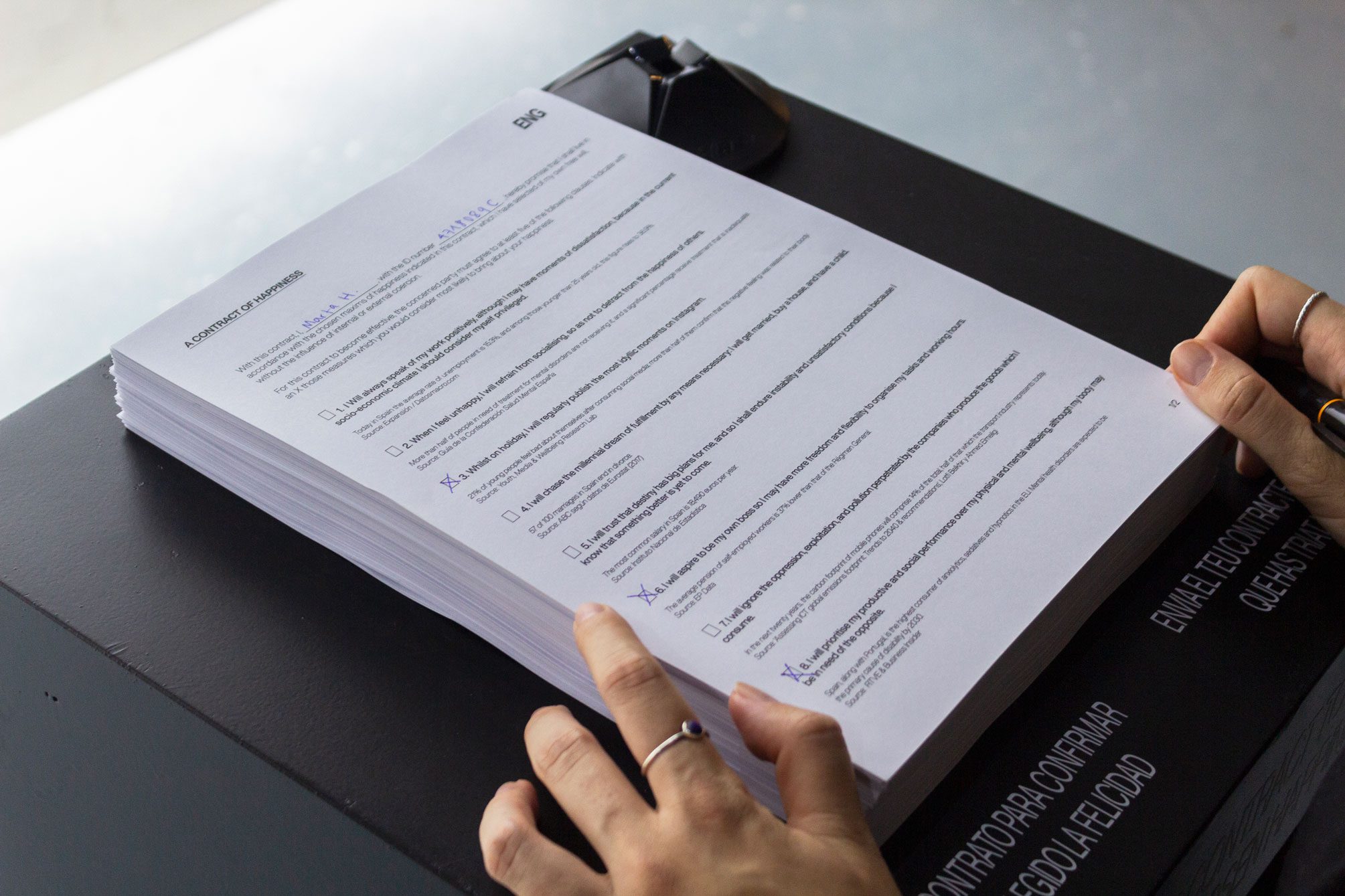

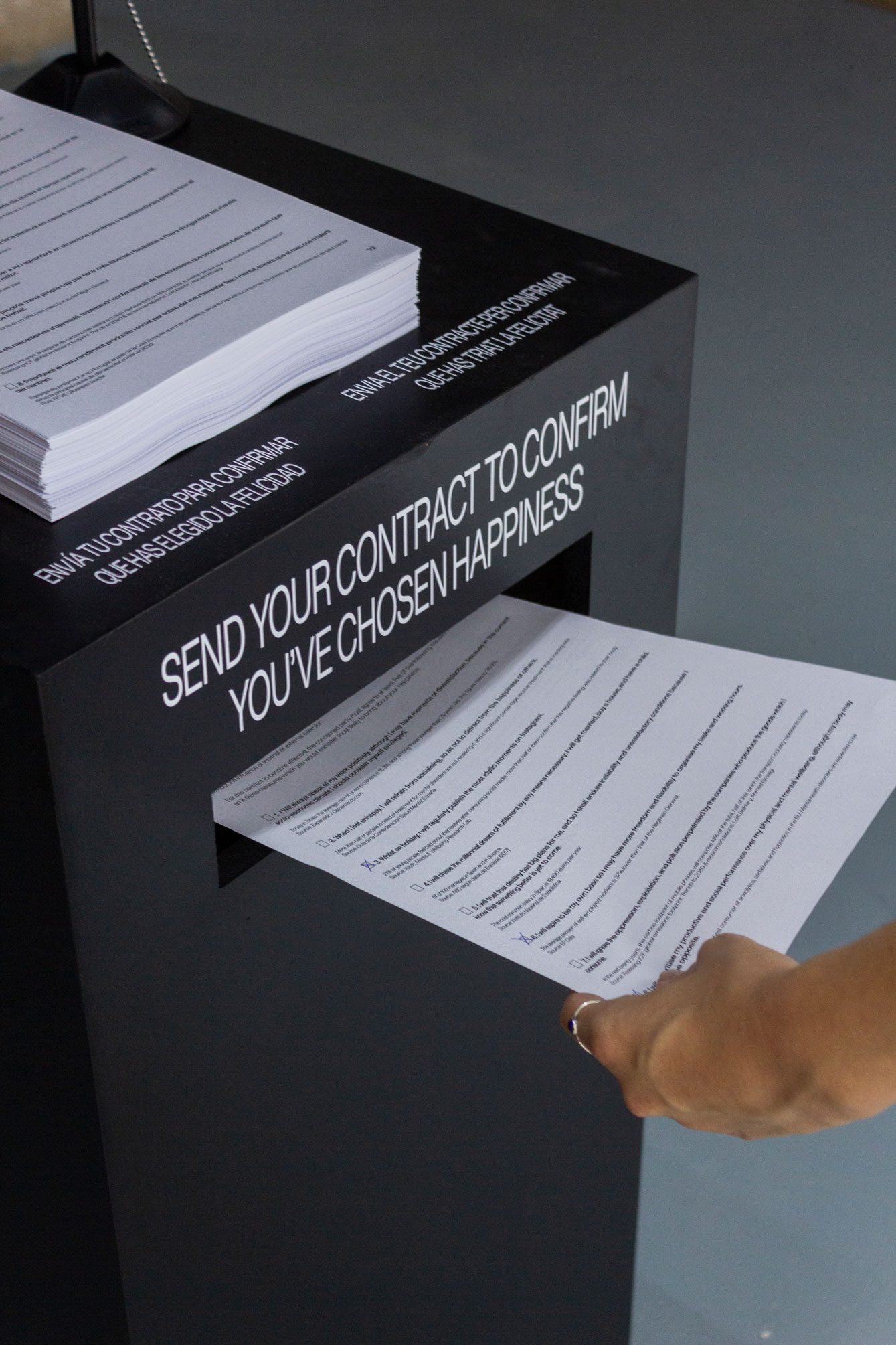

At the end of the room, you can see a phrase written on the wall: "Choose Happiness". Byung-Chul Han and Sarah Ahmed's idea of "the violence of happiness" is captured in a symbolic happiness contract that points to the violence generated by the social obligation to be happy and by the happiness industry. Spain is, along with Portugal, the country in the European Union that consumes the most anxiolytics, sedatives and hypnotics. Mental health problems are expected to be the leading cause of disability in the world in 2030. The question posed by the piece is clear, what are we accepting when we accept happiness?

The exhibition closes with a piece that deals with violence by omission which is, according to catalan journalist and social activist David Fernández, one of the most dangerous we face today. This type of violence occurs in situations of negligence or inaction and indicates that, by ignoring violence, we perpetuate systemic structures of oppression.

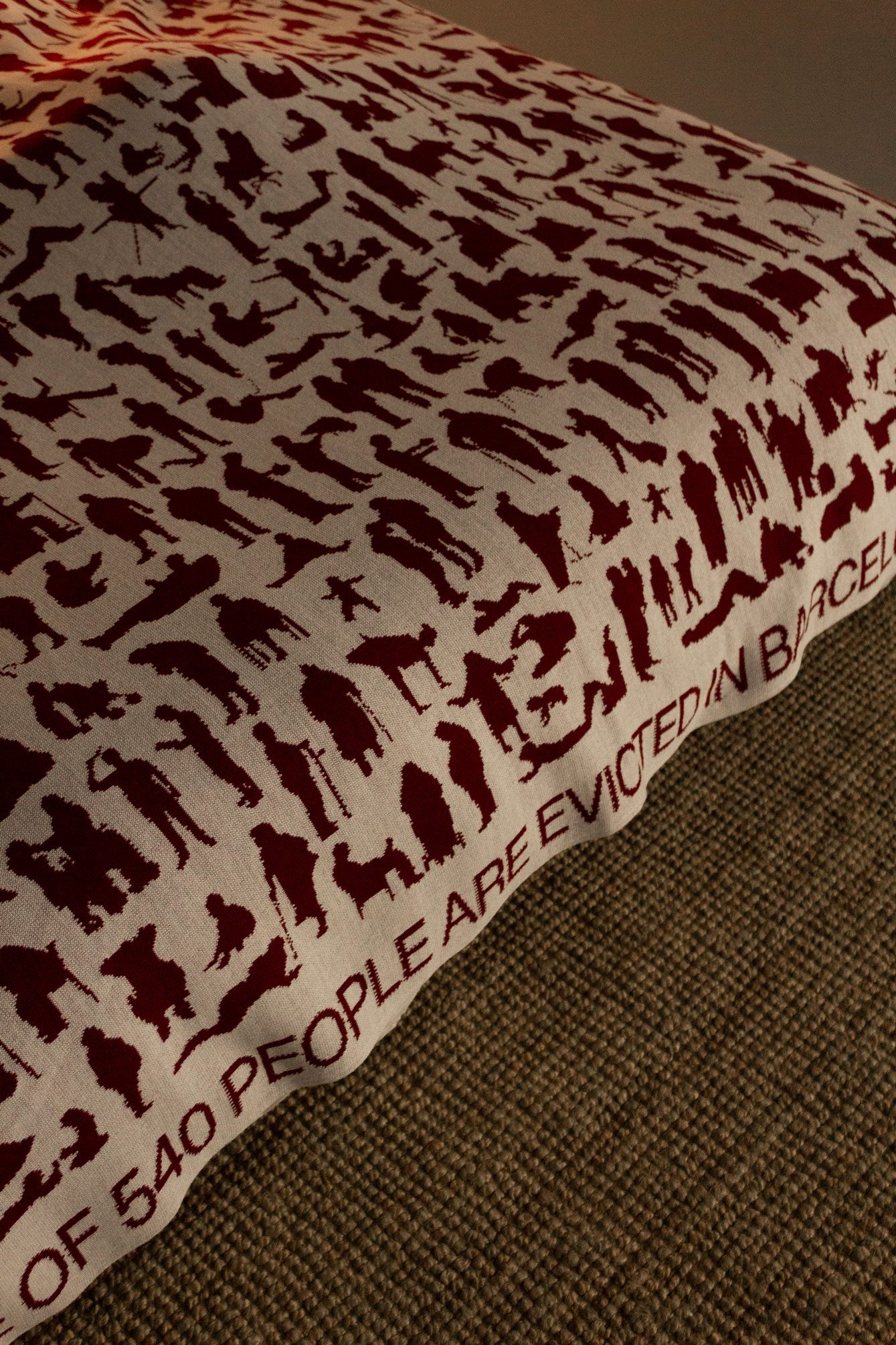

The piece that accompanies the violence is simple: A bed. A resting place that seems normal until you look at the blanket. It is stamped with silhouettes that visualize the number of evictions that there are each month in Barcelona: 540.

540 evictions per month and, even so, we sleep well at night.

730 Hours of Violence

Can society exist without violence?

Number of answers:

*730 hours of violence is part of the MediaFutures project.

This project has received funding from the European Union’s framework Horizon 2020 for research and innovation programme under grant agreement No 951962.

The information reflects the author’s views. The European Commission is not liable for any use that may be made of the information contained therein.