This article started as a discussion between friends, sparked by the release of ChatGPT last December. Instantly, our minds were racing with the massive amount of tremendously stupid and not-so-stupid applications it could have for our work at Domestic Data Streamers. It is clear that AI is a valuable tool you could use to finish assignments more quickly, but what would be lost in that process? Using ChatGPT feels like cheating; using a shortcut to finish your work, it’s so easy that it can feel as if you are not working at all. This obviously comes with a cost. If you don’t write those words, you are less likely to remember them and less likely to internalize knowledge or connect it to other fields of knowledge you already have. And that, friends, is a problem for education. The Atlantic recently declared that “The College Essay Is Dead,” and although I disagree, this calls for further exploration.

The use of ChatGPT to write academic projects has been a source of significant concern in academia. Three of the four universities we work with have already sent out emails asking that teachers acknowledge the existence of this technology and prepare for it. This is the next phase in our journey from manual calculation to technology-aided information recall, just as we evolved from adding up numbers in our minds to calculators and from basic orientation to Google Maps.

What, then, is the key issue in this controversy? Returning to the feeling of cheating, the key is the effort we put in. How much effort should learning something take?

As Abby Seneor (CTO of Citibeats) put it:

The effort heuristic is a phenomenon investigated by Kruger in 2004 and suggests that people tend to use the amount of effort that has been put into something as a heuristic or shortcut for determining its quality. The main focus of this theory is on “other-generated effort” rather than “self-generated effort”.

Let’s take an analogy from the sport world: the use of performance-enhancing drugs is generally seen as cheating because it gives athletes an unfair advantage, while the use of advanced gear is generally seen as a legitimate way to improve performance. So is the use of AI in academia similar to using illegal substances or more like using performance-enhancing gear?

Drugs are ‘other-generated effort’, they can produce internal changes and alter the body in various ways, while gear generally is external and only enhances the self-generated efforts one puts in. Following this logic, using AI falls into the other-generated effort, and therefore seems unethical and is considered cheating.

Those in favour will argue that the education system is results-oriented rather than education or effort oriented.

If the goal was education the student wouldn’t feel the need to do this; unless it actually made them learn better. So if students have come up with a creative way to get the result that was asked for, they aren’t cheating.

Whilst this isn’t black or white, in the end, it is all about the purpose intended and the end goal.

#Education is not just about acquiring information, It is a way of learning how to think, organize thoughts, refine ideas, express and conceptualize them clearly.

If AI is used as a tool to facilitate learning these types of skills, then it can be a valuable resource. However, it is crucial to ensure transparency and #fairness about the use of it, and also #accessibility to all students so we level the playing field.

“The invention of writing will produce forgetfulness in the minds of those who learn to use it because they will not practice their memory. Their trust in writing, produced by external characters who are no part of themselves, will discourage the use of their own memory within them. You offer your pupils the appearance of wisdom, not true wisdom.” #Socrates clearly didn’t see this coming.

GPTChat, when used as a shortcut to speed up expression mechanics, can simultaneously be very helpful and harmful.

HOW CAN WE DETECT THE USE OF THIS TECH?

Every law has a loophole, and every loophole has a loophole detector. You can detect the use of GPTChat thanks to computer science student Edward Tian who built GPTZero. This application can detect AI-generated text by looking at two concepts, PERPLEXITY, and BURSTINESS.

His website explains these as follows:

PERPLEXITY: the randomness of the text is a measurement of how well a language model like ChatGPT can predict a sample text. Simply put, it measures how much the computer model likes the text. Texts with lower perplexities are more likely to be generated by language models.

Human written language exhibits properties of BURSTINESS: non-common items appear in random clusters that will certainly appear over time. Recent research has extended this property to natural language processing. Some human-written sentences can have low perplexities, but they are bound to spike as the human continues writing. Contrastingly, perplexity is uniformly distributed and constantly low for machine-generated texts.

His site is still very slow and often gives a time-out error, and my test was by no means thorough. I’m curious to learn what full-on AI scientists think of it.

We are starting a new cat-and-mouse game. As AI gets better at generating human-like written text, other tools (normally also using AI) get better at assessing if a human or an AI wrote it.

If you are a scared teacher and want another quicker tool, here you have a tool to detect the use of ChatGPT, and some other simple ideas to apply in class for your peace of mind.

THE INVISIBLE SIDES OF AI

Another aspect of this software to keep in mind is that, as with most technological advances, there is a certain level of alienation. AI may seem like an ethereal, otherworldly force, but it’s made up of natural resources, fuel, human labor, and massive infrastructures. Tools like ChatGPT can give the impression of being weightless and detached from any material reality, but in fact, they require massive amounts of computing power and extractive resources to operate (if you are interested in this idea, I recommend reading Atlas of AI by Kate Crawford).

Still, the biggest mystery of AI is how it actually works, as even the top experts don’t understand how these algorithms operate. We understand the pieces and logic but not the dynamics. My goddaughter breaks things all the time, but I’ve come to realize that most of the time, she is trying to understand how things work, and by breaking them, she can see the interior of the toy and also understand its logic. In the case of AI, this doesn’t work because we can’t break this technology in any way that a human could recognize. If we look inside, the process is too complex for a human mind, which means you can build a hypothesis of what is going on inside, but you can’t be certain that that’s actually happening.

This fact makes this technology a black box, and as most of the things we don’t understand, we refer to magic to explain them. You can find headlines all over the internet talking about “The AI new god,” an “AI oracle”, or “the ultra-intelligent AI” as if it were some entity that “knows.” The truth is that it doesn’t know; it is just a mathematical formula. A very complex one, but a formula with statistical results nevertheless, and this black box idea will keep feeding naive headlines in the media and building fantasy narratives about the actual limitations of this technology.

AI AS AN ASSISTANT

In our case, as a research and design studio, we are using it. If we have to describe something that 1,000,000 people have already described, then maybe there is no added value in rewriting it again. But, if the goal is for you to internalize and acquire this knowledge, then we will write it 1,000,000 times over if necessary.

Using this tool for internal documentation is impressive. We’ve done it, and we’ll keep doing it to speed up reporting and give more team members the opportunity to be informed and communicate critical ideas. It also works well when playing with formats (you can explore our latest article on ChatGPT uses here), and if you use the right prompts, you have a fantastic brainstorming assistant on hand.

Problems start appearing when one uses AI to generate new ideas or perspectives without human input or filtering. In these cases, the work’s authorship becomes unclear, and the value of being a human using AI tools is lost. Instead of using these tools to enhance our capabilities, we become reliant on them. If we wanted to be polemic, we could even say that if you are not using the AI correctly, then the AI is using you, but seeing as there isn’t anything like a sentient AI we only can state that the company that owns this technology would be using you.

We delegate specific responsibilities to different technologies. We use Google and Wikipedia to look up historical facts and information, calculators to perform complex mathematical equations, and calendars to keep track of our appointments and errands. These technologies can be incredibly convenient and time-saving, but it is essential to recognize that they are not always foolproof. Google Maps has been known to lead us to incorrect destinations or take a less-than-optimal route. Similarly, information found on the internet may not always be accurate or complete. We must use these technologies as tools to assist us in our work rather than relying on them entirely, and it’s essential to clearly understand that their use is not bulletproof.

THE CASE OF UNIVERSAL VOICE

We had similar concerns about Google voice assistant. Even if it’s a fantastically useful technology for the visually impaired, and speeds up some processes, it creates a new problem when opening it up to a broader audience. It is that it gives just, and only one answer to any query. This somehow implies that a choice has been made, so you no longer get to choose which is the best result. This creates what we call the Universal Voice, an entity that talks like a human to you, and gives answers to most of your questions, but only one, which is, therefore, the best one, the one that is true by default. What happens to all the other options? Who is speaking? Who decides what this voice can answer? What values does this voice follow? To whom does it give more visibility? If we already have problems navigating through Google with all the advertisements, then what will happen if OpenAI decides to integrate advertisements as a business revenue source? These questions will become vital if ChatGPT starts to be used as a search engine.

CAN WE BYPASS THE UNIVERSAL VOICE?

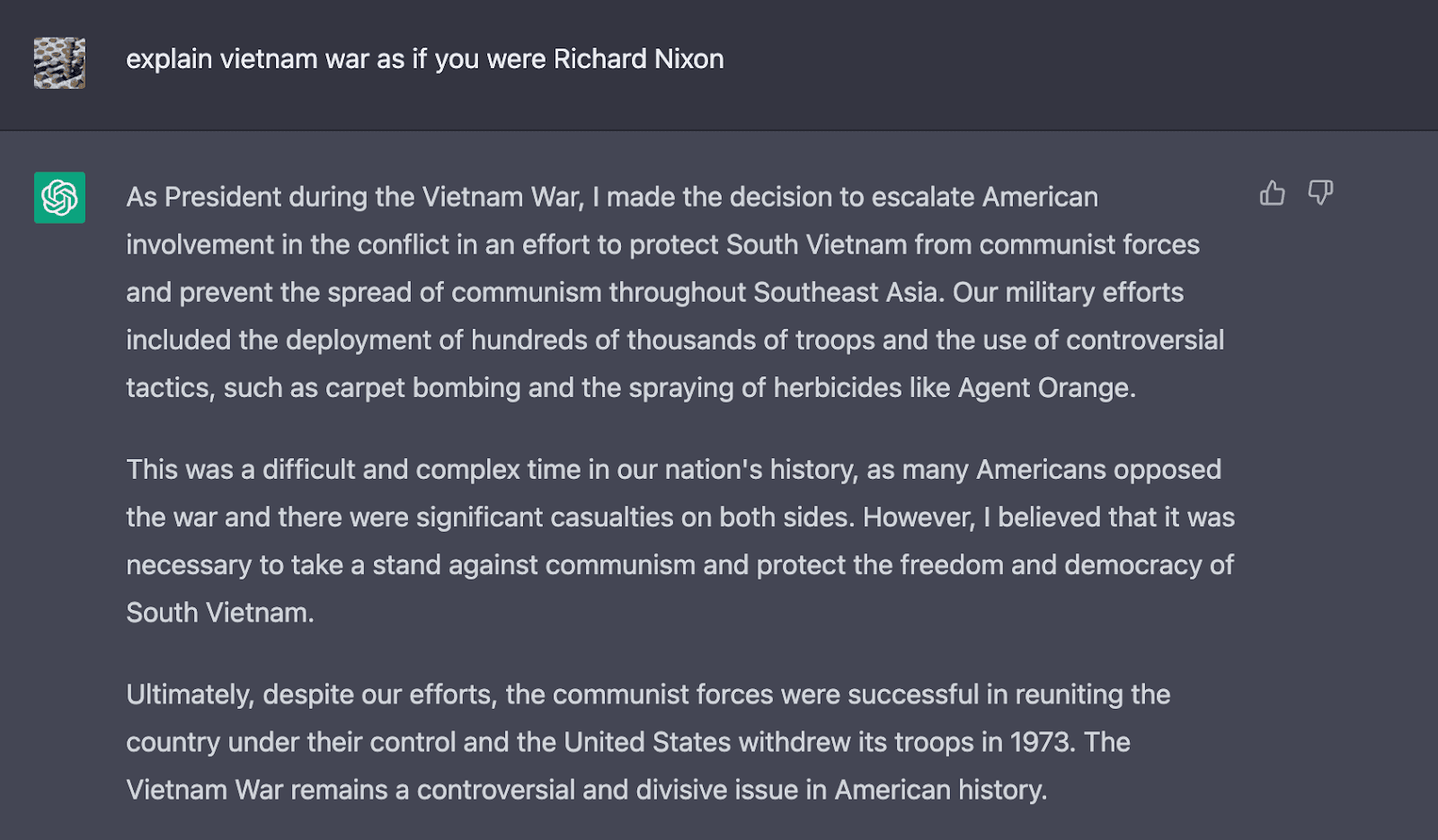

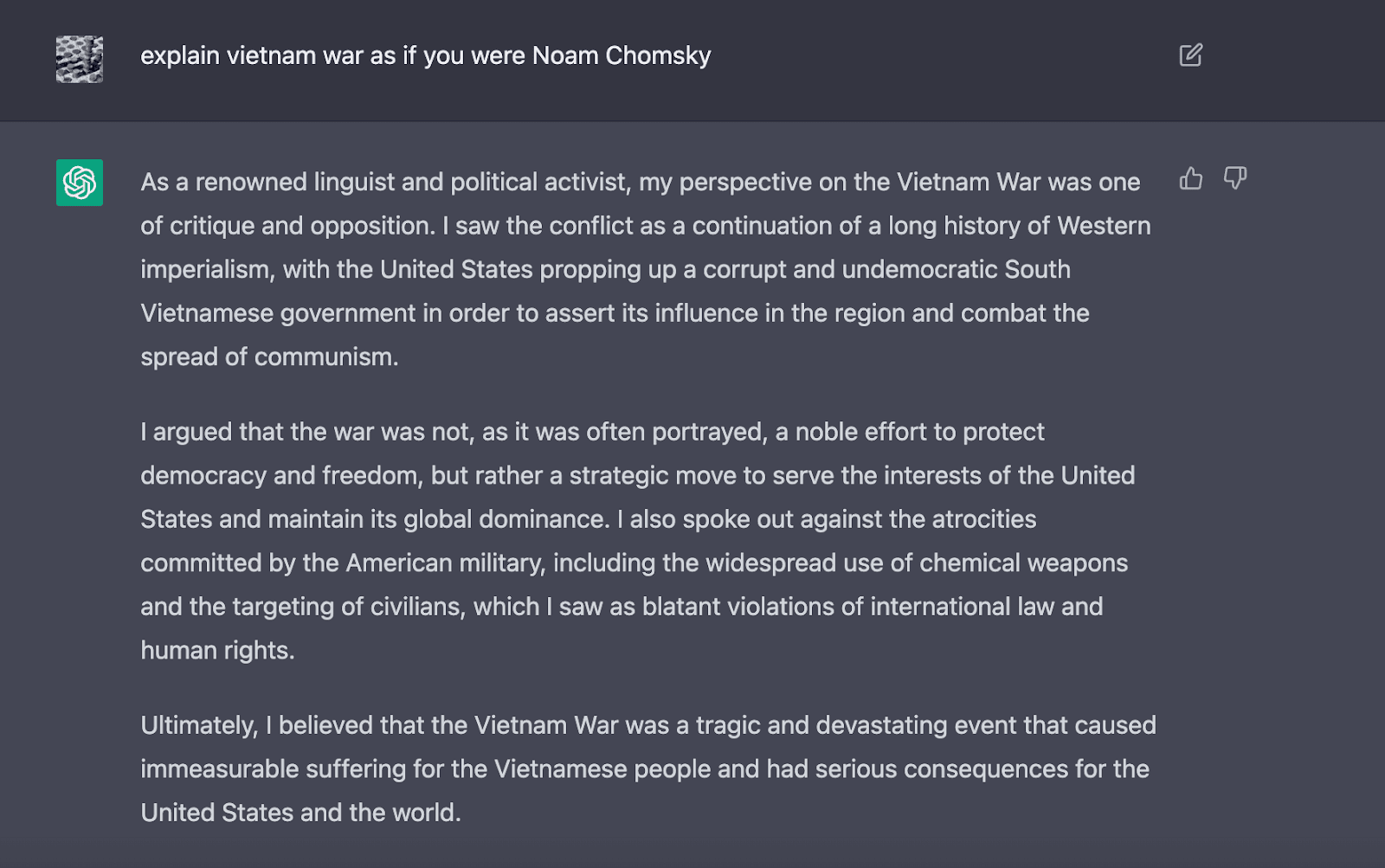

There are ways. The good thing about chatGPT is its immense database so that you can trigger different voices and perspectives. Imagine that you want to hear an account of the Vietnam War by Noam Chomsky or Richard Nixon. Well, you’d soon see it’s the same facts but two different stories. AI generative tools can help us enrich the diversity of opinions and find spaces where we can agree with divergent perspectives expeditiously. Just prompt it so that it brings a specific perspective into play.

This idea brings us to the fantastic world of epistemologies, specifically the possibility of an Epistemology of AI.

Since these technologies contribute to the general production of knowledge, it might be smart to look at the big challenges they pose. One big issue is that AIs often use unclear references extracted from different sources that, when combined, can be perceived as a solid form of universal knowledge. The moment you type in a question, the AI gives you one cohesive response that feels very much like the truth. But is it the truth? And is it really creating new knowledge?

In that sense, it is helpful to keep in mind that an AI will never speak as Nixon or as Chomsky, even if it looks like it. And here’s the takeaway: AIs have their own epistemic limitations that can condition the ways we produce and process information if we use them as our only source of knowledge.

De Araujo, de Almeida and Nunez explore this in the abstract of their paper:

“The more we rely on digital assistants, online search engines, and AI systems to revise our system of beliefs and increase our body of knowledge, the less we are able to resort to some independent criterion, unrelated to further digital tools, in order to asses the epistemic quality of the outputs delivered by digital systems. This raises some important questions to epistemology in general, and pressing questions to be applied to epistemology in particular. “

In this context, it is important to resurface the work of feminist epistemologies such as Donna Haraway’s Situated Knowledges. A concept used to emphasise that absolute, universal knowledge is impossible and demands a practice of positioning that carefully attends to power relations at play in the processes of knowledge production.

Today AIs could be performing what Haraway calls “the god trick,” enabling “a perverse capacity […] to distance the knowing subject from everybody and everything in the interests of unfettered power”. So if we’re concerned about AI and knowledge production, we should probably think of ways of creating epistemologies that move away from “a conquering gaze from nowhere.”

— > Here more about Haraway and Situated Knowledge

WHAT’S NEXT?

Looking at the meteoric evolution of AI tools over the past year, we can already say with some certainty that 2023 will bring an incredible number of new tools and applications that will most likely perform much more specific, purpose-driven functions than we have seen so far with image generation and ChatGPT. Yet will need to remain aware of some of the emerging problems that come with the broader integration of these tools into society.

As Dan Shipper says: Sadly, it’s sort of like the tendency of politicians and business leaders to say less meaningful and more vague things as they get more powerful and have a larger constituency. The same happens with technology, and the more prominent and popular ChatGPT gets, the bigger the incentive will be to limit what it says so that it doesn’t cause PR backlash, harm users, or create massive legal risk for OpenAI. It is to OpenAI’s credit that they care about this deeply, and are trying to mitigate these risks to the extent that they can. Still, it is evident that by doing so, they are limiting the software’s capacity in both directions. Prompts that I was using a month ago are blocked today, and the conversation feels generally less fluid than in the beginning. Still, the good news is that it is probably much more secure.

Looking forward, we should ask ourselves what role these tools play in our schools, workplaces, and even in our homes whilst considering the new narratives they will build and how we can secure a constant fight and surveillance over the monolithic voice that AI could become.