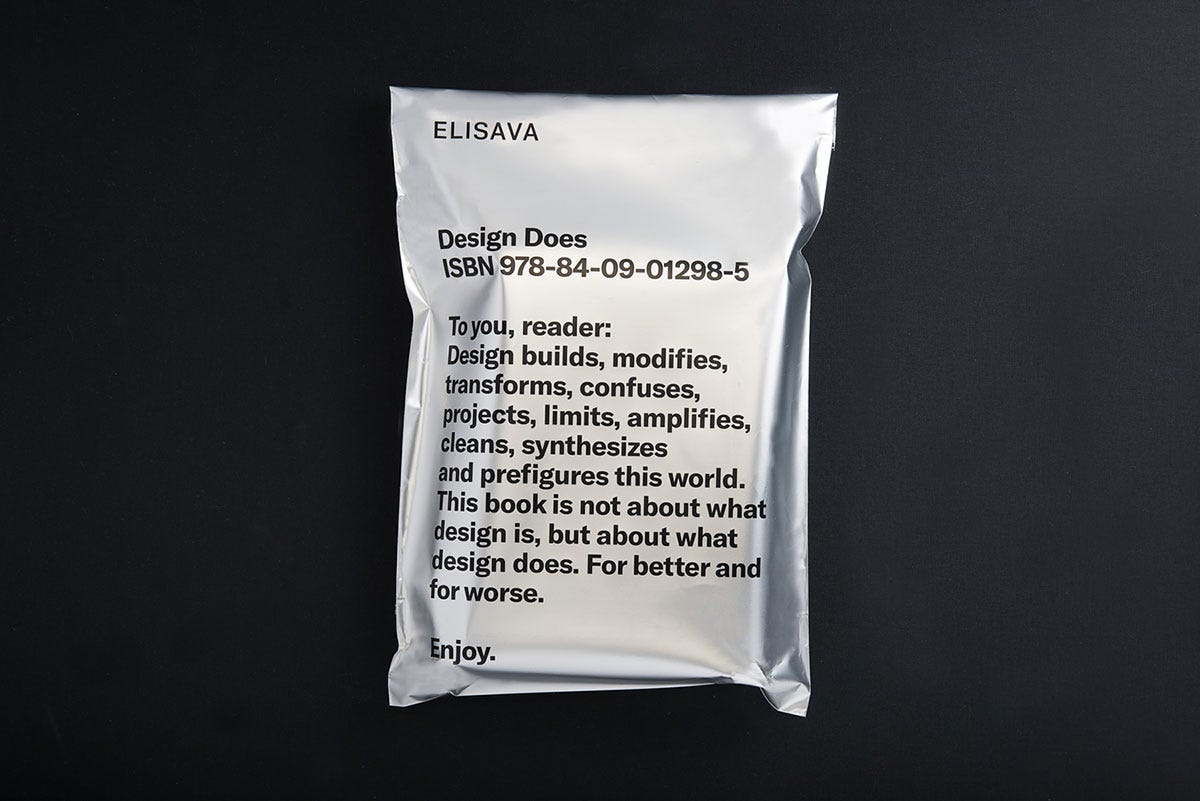

This is article is part of the chapter “What we need to persuade” on the book Design Does: For Better and for worse.

This article was originally going to be titled “What do we need to persuade?”, but this was immediately replaced with the current title, as to be able to persuade you need empathy, and we wanted to reveal the vast domain design covers for exploring empathy.

Empathy, in the world of design, is not what is commonly understood as such, i.e., ergonomic empathy; it’s not about designing so that someone has an amazing experience each time they use a particular chair, but rather seeking the user’s emotional acceptance; that is to say, accepting and enhancing what the user feels and desires by entering into the most visceral of subjective perceptions and experiences. In this article, we deal specifically with moments of empathy that go beyond the physical or graphic interface of a design, and which focus on the intentions and connections that these design objects are able to generate.

The technological and social advances of the past 20 years have given us extraordinarily powerful tools for rediscovering the concept of empathy in design. However, as has often been the case with great achievements of the human race, it has been mainly by chance or error that these tools have seen the light of day. A particularly interesting case stemmed from a comment on YouTube posted on a video on Xbox video games; I remember it as my first direct confrontation with the emotionality that can arise from something as apparently mundane as a video game.

The comment consisted of the following story:

Youtube user 00WARTHERAPY00:

Well, when i was 4, my dad bought a trusty XBox. you know, the first, ruggedy, blocky one from 2001. we had tons and tons and tons of fun playing all kinds of games together — until he died, when i was just 6.

i couldnt touch that console for 10 years.

but once i did, i noticed something.

we used to play a racing game, Rally Sports Challenge. actually pretty awesome for the time it came. and once i started meddling around…

i found a GHOST.

literally.

you know, when a time race happens, that the fastest lap so far gets recorded as a ghost driver? yep, you guessed it — his ghost still rolls around the track today. and so i played and played, and played, untill i was almost able to beat the ghost. until one day i got ahead of it, i sur- passed it, and…

i stopped right in front of the finish line, just to ensure i wouldnt delete it.

Bliss.

I’m convinced that when they developed this video game, Microsoft had no idea that their design could become the nexus between a father and his son from beyond the grave. Suddenly, the feature developed to improve your lap times on a car-racing video game, became a way of reconnecting with a loved one, with whom you can no longer interact. There are endless examples of this, where a tool becomes a system of personal connection sufficiently intense to have a major impact on a person’s life.

Understanding that all designs can become relational artifacts helps us to see the potential design has beyond the primary function often afforded it. The challenge lies in seek- ing out these spaces, giving them greater strength and focus and taking their currently anecdotal capacity for connection and transforming it into another part of the design, into a conceived feature.

By interpreting design as a form of language, of expressing thoughts, we can understand it on different metaphorical levels. On a first level we have the expression of objects or tools (words); on a second level, the expression of systems or families (sentences and grammar); and on a third level, the emotional interpretation of design (the discourse). We thereby see how design, interpreted as a form of human expression, can be subject to the rules of language.

Understanding design as an open language exposed to the virtues and defects of human thought allows us to under- stand the true vastness of design and what it has the potential to do. This opens up the possibility that anything we design can be interpreted by each individual who interacts with it, through the filter of their memories, emotions, fears, desires and, basically, their thoughts.

Staying with the language metaphor, we can approach the design of a video game in the understanding that, like words, this will have both a denotation and connotation. Empathic design requires us to find out what things can evoke and encourages the designer to speculate, to anticipate what their design might arouse emotionally through connotation in contexts that are beyond their control.

Working with connotation allows us to generate emotional scenarios, and these scenarios can be facilitated if part of the design represents the existence of another person. The example of the video game is clear, but in the case of, let’s say, a chair, we could perhaps observe that if one of the children in a family sets aside a chair that the rest of the family recognizes as being theirs, the chair will always have the connotation of the child that claimed it as their own. What would happen if all the children chose a chair when they turned 10? The object would no longer be a chair, instead becoming some- thing that marks the 10th birthday of each of the children. If we further complicate this example, we could begin to think about the meaning of the emotional design of something more complex, like a work post, a communications campaign or an entire organisation. The possibilities are infinite and the behavioral engineering necessary to understand what is happening must be on a par with the complexity of the designed system or discourse.

So, when we talk about emotional design, we are referring to the possibility that emotions are expressed, transmitted or interpreted in a part of the design, whether a deliberately included feature or not. Emotional design comprises the wonderful act of understanding the emotions and human realities that take place in a design’s contemporary setting. It represents people’s feelings and allows users to take owner- ship of the meaning of things through a dialogue and space of interaction with the designed object. For this to flow, it would suffice to do something as simple as fall in love with the kind of user you have in mind: if you design sofas, fall in love with couch potatoes; if you’re a teacher and you design classes, fall in love with the students; if you’re a video game designer, fall in love with the players; and if you’re a designer of organizations, fall in love with the workers. Falling in love with your target users is the best way to get into a designer’s intuitive mindset and understand and empathize through the users’ emotions.

In the last decade, we’ve seen how big companies from the sector, like IDEO, Frog Design or Designit, have placed humans at the center of any decision, waving the flag of empathy.

The job of the designer is to convert need into demand, just figure out what people need and give it to them. I would suggest that we need to return human beings to the center of the story. We need to learn to put people first.

- Peter Drucker

This is not an isolated movement. Without intending to sound alarmist, in the last 15 years, 51% of the companies on the Fortune 500 Companies lists have disappeared, and, those that remain, have either a philosophy centered on the product or the figure of the consumer or one based on relationships and the role that companies have in these. Google, Netflix, Spotify, Airbnb or IBM are the epitomes of this change in paradigm.

The organizations that get the best results are those capable of sensitively interpreting the users’ emotional needs, and to do this there is only one valid starting point: understanding what they are feeling. With this premise in mind, we can all empathize with the idea of holding a conversation or having a relationship with someone that you know knows you and responds to you with your reality in mind.

In the world of business, this is only possible when we understand services as the ideal platform for speaking to clients about what they are thinking, feeling or suffering. Understanding clients’ feelings through the course of a relationship is something that small businesses have always done , as have systems in which the company has a close relationship with the client. Today, technology gives us the opportunity to broaden this scale. The engineering of knowledge through the interpretation of client data allows us to analyses and make predictive models, but, how can we interpret data in a way that is sensitive?

Just as relational design is changing how we approach the world, we can also analyses the consequences of an absence of empathy and relational design. Four years ago, an emerging artist gave a conference at the University of Berkeley. He had traveled around half the world working on music projects with people suffering from some kind of hearing disability. The artist noticed the immense lack of lexical tools and communication spaces between the deaf and the hearing. He said that on one of his last projects, in the Middle East, he had worked with a group of young people aged between 13 and 18, to whom he had given voice recorders. The group had to go around the city recording what they wanted to hear. The artist subsequently reproduced the sounds through vibrations using an instrument built from different rubber spheres. Some of the young people, who were deaf, recorded things that, as a rule, don’t emit sound; like a wall, a lamp or a mirror. Others, with the vibration of the rubbers spheres, were able to detect the sound of a passing ambulance. Suddenly, a world that was apparently only perceivable for those who can hear was made visible, clearing showing that some objects don’t produce sound. The imagination of these young people gave sound to spaces that, to their minds, deserved it.

In any case, what most impressed the artist was the how naturally these young people talked about sex, violence or drugs, theoretically taboo subjects in the Middle East. The deficiencies in language extended to the deaf community allowed them to think more freely, since they were unaware of most of the forms of censorship in their country.

The philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein once said that “the limits of my language are the limits of my world”. In this case, the limits that we establish needn’t be negative, which means if we understand design as a form of language, it can be seen as a tool for connection, as well as one for censorship. The challenge is to develop an awareness of this new sphere of design, which will increasingly affect our way of living.