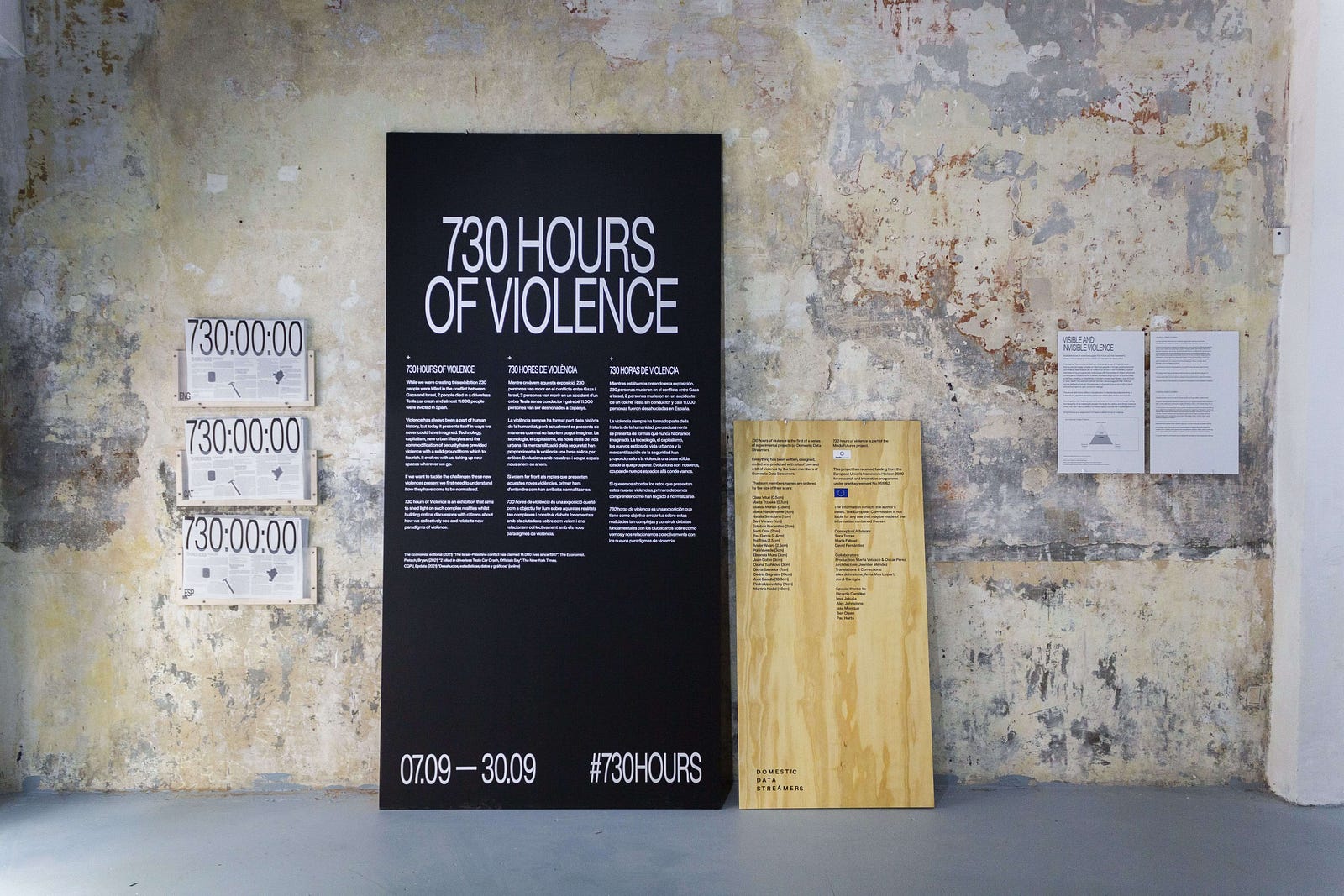

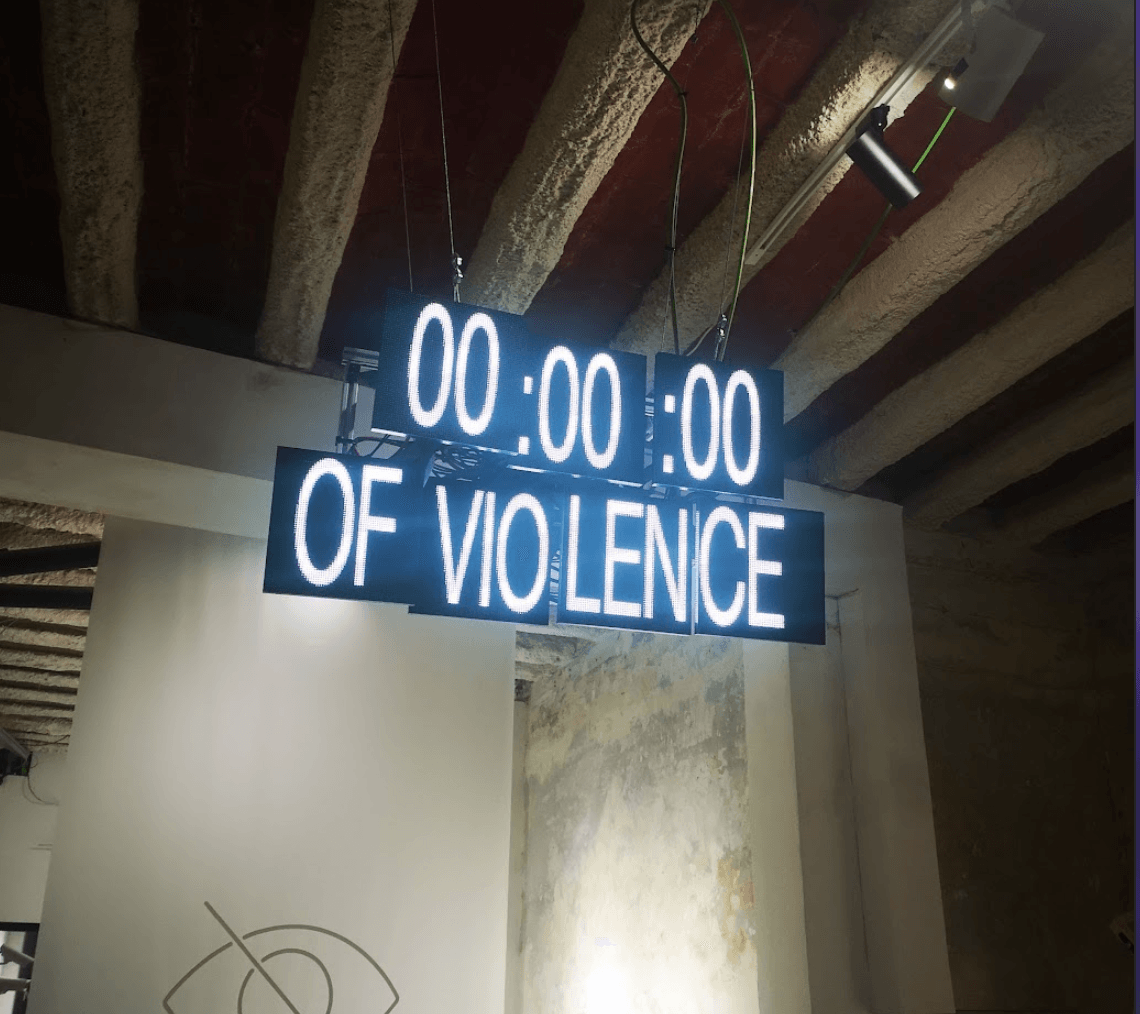

On the 30th of September, the countdown of our exhibition “730 hours of violence” reached 0, bringing to an end the first iteration of the #730hours initiative. In a typical DDS fashion, this was not your average exhibition of framed pictures on a wall, but an opportunity to collect visitor’s responses to key questions about violence.

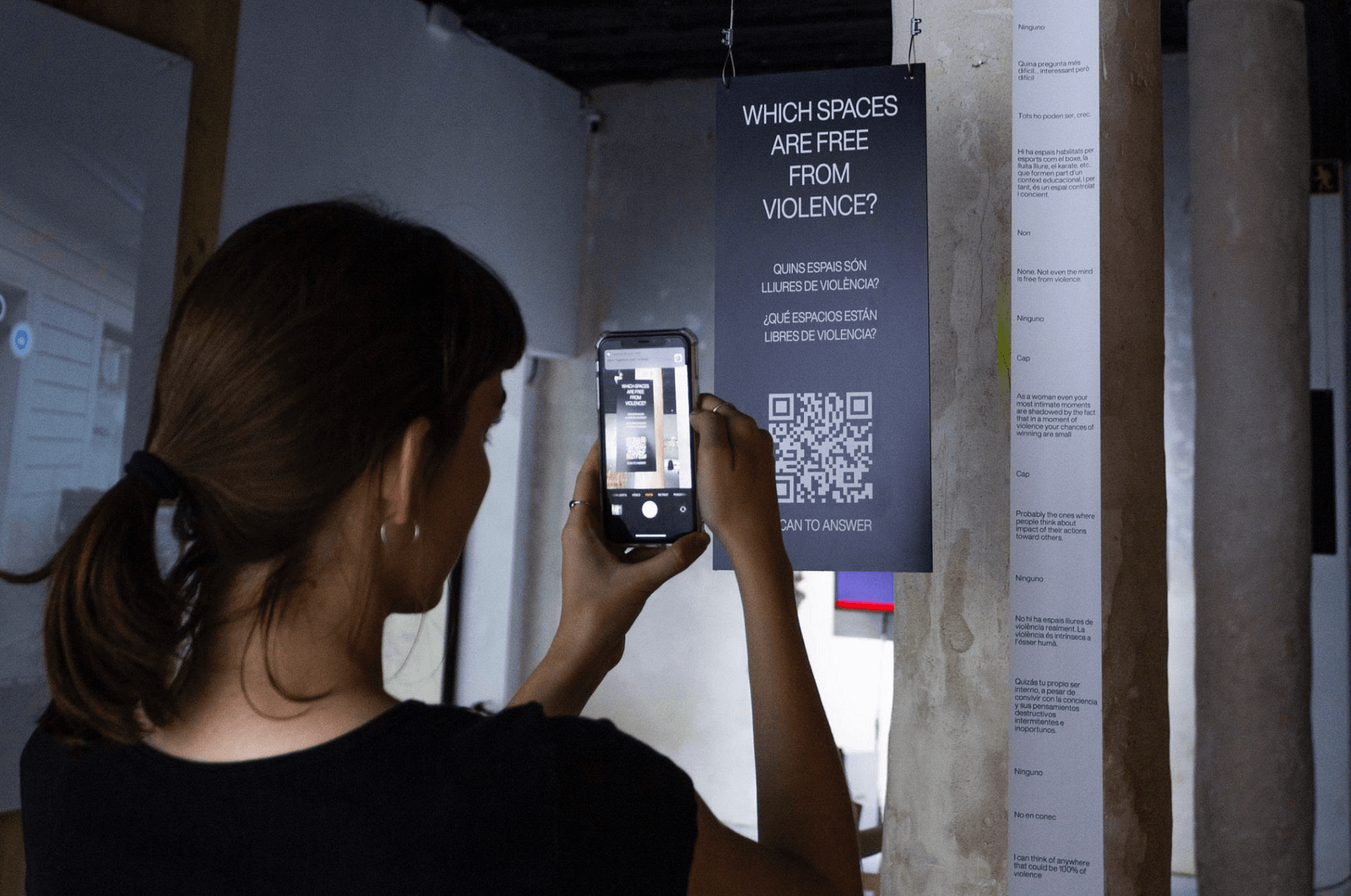

The system went like this: At six points in the journey the public was able to answer six different questions related to violence. They spoke to us, and we collected what they had to share. Easy.

Today, after a month of collecting messages (and a few crazy nights analysing them to turn the individual testimonies into data) there’s a lot we’d like to share with you.

Before getting to the data. Who attended this exhibition?

Through the 730 hours we got over 2,100 visitors. Even if the youngest participant was 10 years old and the eldest 89, we mainly attracted young Barcelona-based people: 80% of our attendees ranged between 20 to 40 years old. What you’re about to read is their own, unique thoughts on contemporary violence. Enjoy.

Question 1: When did you first encounter violence?

As kids. In school. As newborns, even. 30% of the visitors in our exhibition agree: We meet violence for the first time during our childhood. The average answer tells us how, from a very young age, we are exposed to violence as victims (almost as if violence was a learnt conduct that wasn’t part of our lives until someone introduced us to it).

Brothers and sisters who hit us. The moment someone in a hospital identifies us with the wrong gender. Realising that you’re born in a country where your life isn’t worth a dime. Being embarrassed by a teacher for not understanding a lesson…

Scenarios vary but the story remains constant regardless of the respondent’s age: Childhood is a vulnerable period where we learn how the world works around us. And because violence has been a useful tool for our predecessors, we learn it and accept it as part of life. Violence wasn’t there until, suddenly, it was.

Data deep dive:

The most referenced topic is “in my childhood” with around 30% of the respondents talking about it. If we explore the concept of “childhood” further, 15% mention violence in the context of school (4% talk about bullying) and 6.63% identify violence at home.

Other interesting answers are the 8.43% who point to the moment when they were born and the 6.63% who state that they don’t remember.

Question 2: When is violence justified?

Political theorist Norman Geras defended that violence could be justified in the case of grave social injustices: the only possible reason for violence is to avert imminent and certain disaster. In his piece “Our morals” he points out that even when violence may become necessary to prevent an impending moral catastrophe, its use must always remain exceedingly rare and conducted with a very heavy heart.

The debate was polarising: Our visitors either think like Geras or feel that violence can never be justified. Which means that they fundamentally consider violence as a counterproductive phenomena. But there is another interesting angle to the question; those who justify and defend that consensual violence exists.

In what context would someone express their desire to experience violence, though? “BDSM”. “Mixed Martial Arts and other contact sports” or “Surgeries”, for example. Spaces that become accepted and tolerable through social and cultural processes.

Data deep dive:

Top mentions are split: Self-defense has the highest number of mentions with 27.6% of answers.

No justification at all got 21.1% responses. Life protection goes after that with 10.6%.

Other related concepts that stand out are: When rights are violated [5.9%] (people mostly talk about humans, but references to environmental and animal rights were made), When there’s people in danger [4.9%] and to survive [4.9%].

Question 03: Why do we like violence?

Even if we formulated the question by assuming that we’re highly attracted to violence, our visitors mostly disagreed: 20,7% of answers stated that they “don’t like violence”.

Then, how can we explain the rise of on-demand violent content that’s being generated on media platforms such as Netflix? The streaming service’s data shows that people love death and violence-centered content: 2 out of the top 3 binged shows in 2018 were scripted to focus on murders and suicide, and half of the most watched original productions in the same year contained a significant degree of violence or morbid themes. But we’re not just talking about films: A study revealed that 88% of popular porn videos contain violence.

Violence-lovers were also present in our exhibition and they told us about its strong aesthetic component and that our obsession with the subject comes from the fact that we live in a society that doesn’t accept violence. The answer may potentially lie somewhere in the origins of human behavior: perhaps, the fascination with violence is a simple result of human curiosity. The majority of us might not consider ourselves violent; yet we are curious to see what lies in the mysterious, unknown underside of our society where the rules are broken without regard to human life or authority.

Data deep dive:

“I don’t like violence” has been the most popular answer, with 20.7% of answers. From those who responded positively, we can highlight two main ideas:

People who say it is because of our Human / Natural condition [10.34%] (similarly, 9.5% of responses think of liking violence as part of our animal “instinct”).

Another interesting perspective is the 13.8% of visitors who talk about the feelings and emotions that violence generates. Our public mentioned power [6.9%], adrenaline [2.6%] or the need to discharge anger [2.6%] as triggers for violence consumption.

Question 04: How do we deactivate violence?

By rethinking our relationship with the world around us, according to our visitors.

When posing this question we were inspired by something philosopher Rosi Braidotti said: “Let’s look at how feminism has taught us to distance ourselves from male violence. Or how anti-racism has taught us to distance ourselves from white supremacism. It’s about distancing yourself. It’s a detox exercise. We need to detoxify ourselves from bad habits of thinking and relating to others.” And it seems that the public is aligned with her views on change.

28,5% of the answers we gathered talk about fighting violence with education and dialogue. 13,9% of participants believe that empathy, love and respect are good solutions. In this context, we asked the public to position themselves on another matter. To the question “Which is a more effective way to combat violence?” 82% of respondents agreed that conversation is a better option over condemnation.

In other debates where we’ve assumed a certain social positioning, the public has strongly disagreed with us. We saw an example of that in the previous question: People didn’t want us to assume they liked violence so they insisted on letting us know. Interestingly, out of 223 responses to this question, no one said there was no need for violence to be deactivated. Does this mean that we see violence as a problem, something intrinsically bad that we need to address?

Data deep dive:

These were the top five reasons stated by the visitors of our exhibition:

With education [17.9%]

With dialogue [10.6%]

With empathy [5.7%]

With love [4.1%]

With respect [4.1%]

Question 5: What spaces are free from violence?

The public was split in two when answering this question. We have the optimists who think that non-contaminated spaces exist, and the Bourdieu fans who defend precisely the opposite.

Most of our visitors belong to the second category: believers that violence is everywhere and not even our minds are free from it. As one of our visitors put it: “I can’t think of any. We are violent even when we talk to ourselves.”

Another thought-provoking idea was repeated in several comments and has to do with distancing ourselves from us. In other words, numerous visitors defend that violence is intrinsic to the human gaze so we must exit the human experience to stop experiencing it. “Any space that is far from Earth”, “Cemeteries” or “The prehistoric period where only bacteria ruled over the planet”. Literally anything that doesn’t involve people.

Answers like these make us ask ourselves: If there is no space free from violence, why aren’t our collective efforts placed on addressing that issue? Are we just assuming this is just who we are as a species? Can’t we do something about it?

Data deep dive:

45.4% of our respondents state that there’s no place free of violence.

Question 06: In what context can violence be useful?

According to our audience, in many. Our public thinks that violence is useful as a form of resistance, an ultimate act that harnesses the power of opposing or withstanding.

From the moment you need to defend yourself, to the situation where you are fighting an injustice; violence can help you keep your position.

The same idea applies to larger systems such as governments and institutions. A participant wrote “States exercise their legitimate monopoly of violence through their armed forces to maintain their hegemony”. Resistance, in this sense, can be understood as a last resort to keep the power structure intact against individual challengers.

Surprisingly though, in the context of the exhibition, violence isn’t read as useful when it presents itself as an intentional act, only as a reaction. So it isn’t a solution unless it is linked to the protection and preservation of bodies or powers.

Data deep dive:

Most submitted answers: In order to defend ourselves or others [14.9%], when fighting injustices [5%] or extreme situations [4%]

And of course you might be asking yourself… How have we analysed this data?

Through our 730hours website and the QRs along the exhibition, we’ve gathered over 1,000 responses that are saved in our ad-hoc database.

In order to transform the qualitative understanding of the content the public has shared to quantitative data, we have used Natural Language Processing (NLP) methodologies to get a rank of the most popular keywords used in each of the questions: grouping by similar words and filtering the low-meaning words to get the most out of the frequent ideas.

The result of the analyses you’ve just read is based on the stream of responses we’ve collected over 730 hours in the context of the “730 hours of violence” exhibition. A report that aims to open new dialogues of violence, contributing to a larger collective discussion.

This piece wouldn’t exist without the generous data contribution made by our visitors so, to everyone that has been a part of this project: thank you for your stories.