This article summarizes key perspectives on the dilemma we are all facing in the creative industries right now regarding using certain generative Artificial Intelligence tools. I’ve been a beta user of these platforms since 2021, I’ve tested most of them, and I’ve followed the meteoric evolution of these tools. Today, rather than focusing on how to use these tools, I want to share the most significant ethical debates that have emerged with regard to their use in the arts and creative sector.

Let’s start with some basic facts:

- AI generative systems are only possible because of the vast datasets of images, videos, and text used to train them, and it is true that a share of this data is available in the public domain. However, a proportion of the data used in these datasets belongs to living artists that have not declared it to be public domain data.

- Therefore these artists are a part of the foundation on which this revolution supports itself on its exponential rise.

- These artists made their living by selling such data i.e. their decades of hard work that have produced a specific style and a series of works.

- Still today, you can replicate hundreds of images with the style of some of these artists, with all the earnings going to the software companies providing the model or the interface.

- Today to do that is 100% legal, so no law is being infringed, which is both good for some and bad for others.

In this article, we will explore arguments on both sides.

CAN YOU FREELY USE AI ART?

The quick answer is yes; you can freely use these images, as Midjourney says: “you own all Assets you create,” but you also allow others to view, use, and rework those images. So basically, you have commercial rights to use your creations, but so does everyone else. In some countries, there are no rights granted to AI-generated art, so all images are essentially in the public domain.

Now there is a limit to this. For example, if you generate a recognizable image of Batman or any public figure, you cannot commercially use that art, because you aren’t the rights holder for Batman.

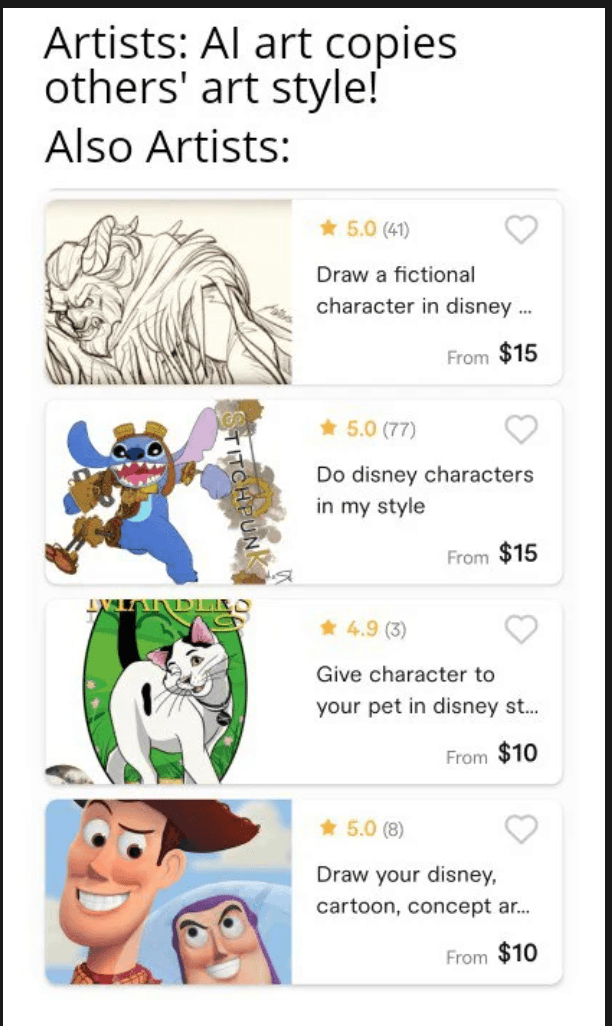

But what about the stylistic traits of a specific artist? The truth is that you can protect an artwork but not a style; protecting an art style is not valid under any copyright system. (Section 310.4 (Style), and 310.9 (composition) respectively.). This limit creates a substantial legal void in which this technology lingers. There is certainly nothing improper with training the AI on a long-dead artist like Leonardo da Vinci, whose works are in the public domain, but can the same be said for a contemporary artist?

OPENING THE DISCUSSION

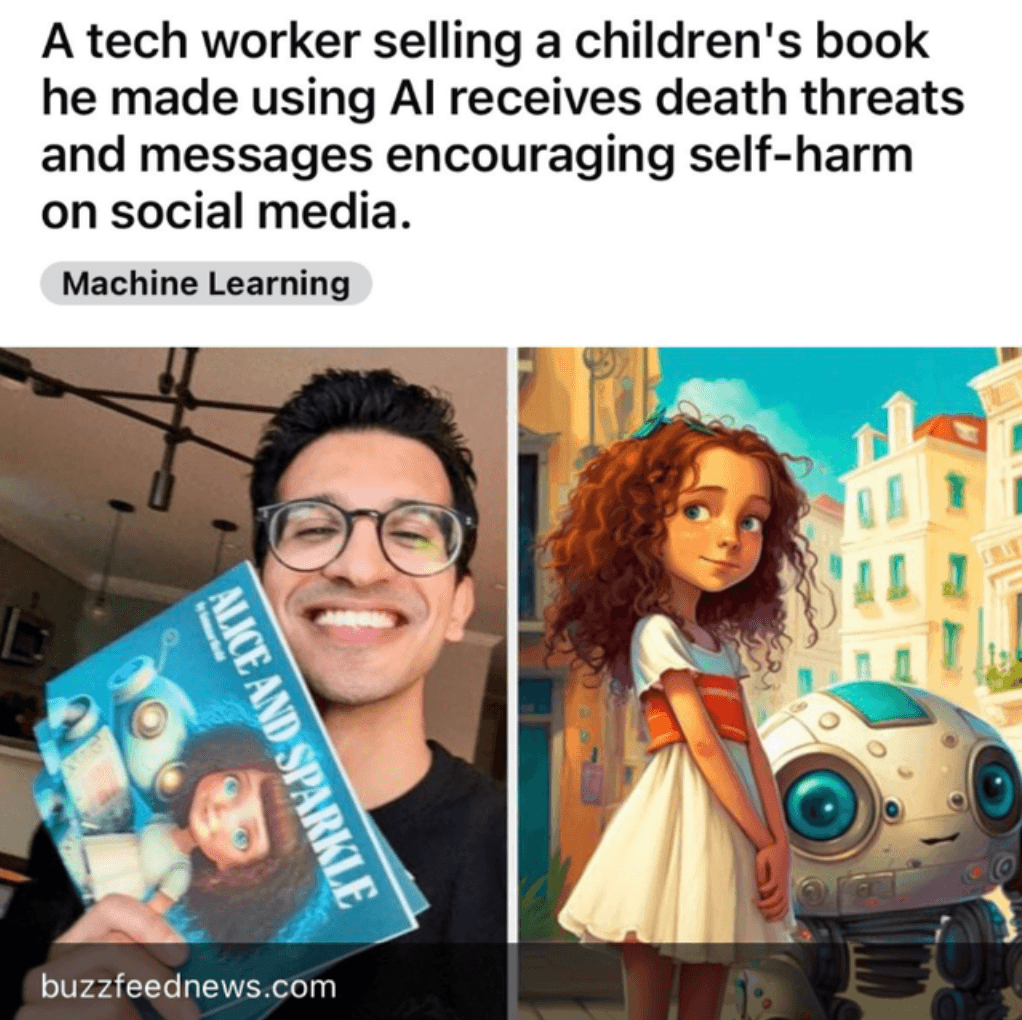

AI has been an ongoing field of study and discussion since the 60’s. But in the last months, a lot has happened. Since around September 2022, there has been a growing gap between more and more artists, illustrators, designers, and other notable people from the creative industry (many of whom I respect and admire greatly), some demonstrating full support and others direct opposition toward generative Artificial Intelligence tools like Dalle2, Stable Diffusion or Midjourney.

The debate and discussion around the role of generative art in the creative industry have been ongoing for many years. Still, when Stable Diffusion started to showcase some high-quality generations in September with almost unrestricted access to everyone, the pot started to boil. Two months later, a final boom of indignation from the creative sector came up with the release of a function in the app Lensa that transforms selfies into impressive digital illustrations, giving access to generative AI tools to a vast mainstream audience (more than 25 million users so far).

But what is Lensa? This app invites you to upload 10–20 images of yourself, and using the open-source model of Stable Diffusion will generate avatars of you that appear to have been created by digital artists. The problem? Stable Diffusion uses part of copyrighted art from artists around the world. It has been trained through the database of the nonprofit research organization LAION. This database includes 5.85 billion uncurated images scraped from the internet from 2014 to 2021, including hundreds of thousands of artists’ artworks. Lensa made $16.2 million in revenue in 2022, with $8 million banked in December alone, of which the original artists have not received a penny.

Another problem is that this boom exists because Stable Diffusion has been very transparent with the origins of its database. However, we cannot say the same for the other two big players, OpenAI and Midjourney, which still today have not disclosed where they scraped all their training images from. All these platforms state that what they are doing is not illegal, and it is not. The question is not if it’s legal but if it is ethical.

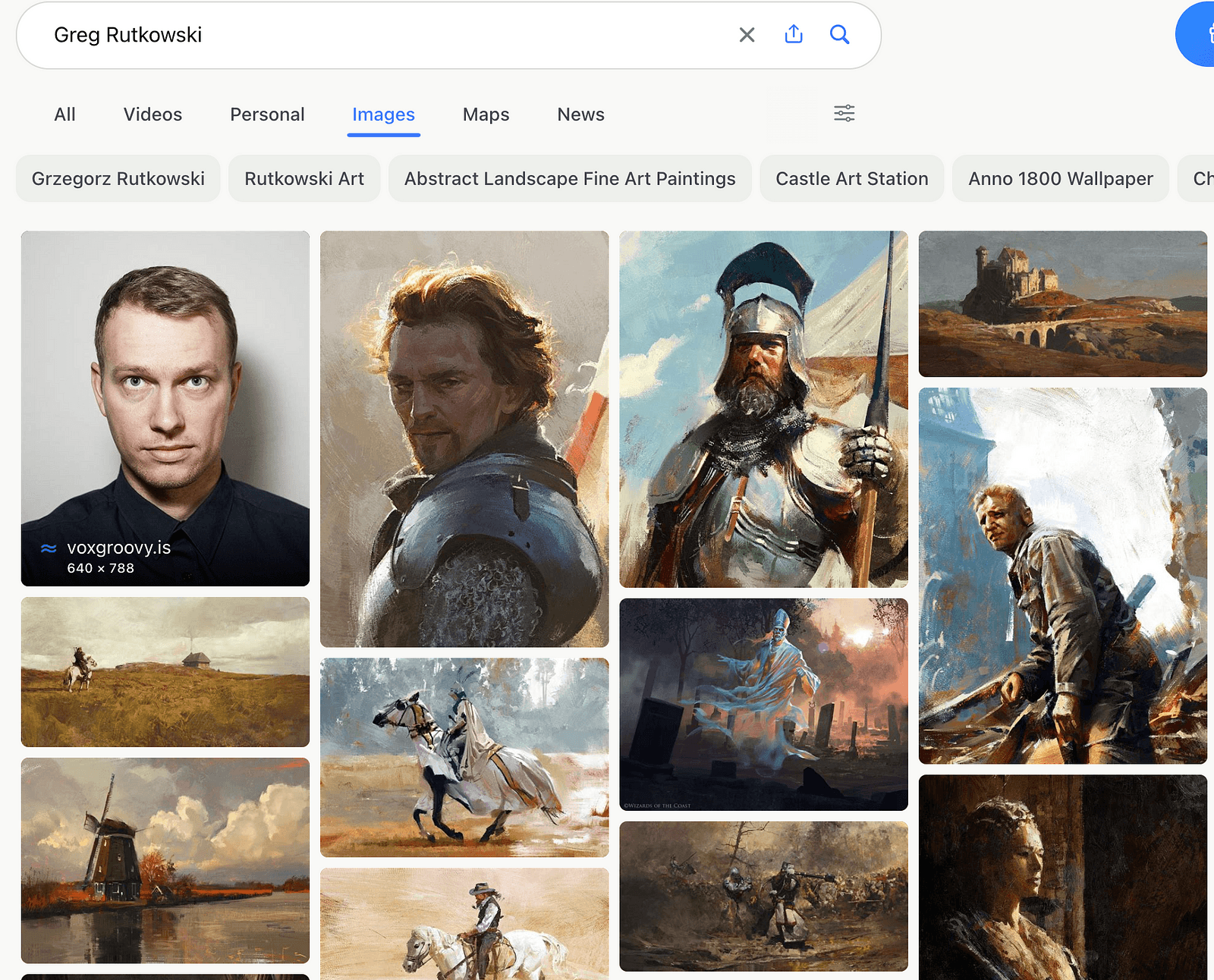

To give you a hint of how these rapid changes are affecting individual artists, we can look at one of the most extreme cases that has come to light. Greg Rutkowski became one of the most used artists in AI generations, firstly because he was used as an example by Disco Diffusion (one of the first of 2022), but also because Rutkowski had added alt text in English when uploading his work online. These descriptions of the images are helpful for people with visual impairments who use screen reader software, and they help search engines rank the images as well. This makes them easy to scrape, and the AI model knows which images are relevant to prompts. His name has been used more than 100.000 times to create images; several opinions state that this is a fantastic way to show the influence of an artist BUT it have some negative aspects, if you search Greg Rutkowski on Google, you will find that he did not create a big chunk of the work shown.

You can actually take the open source model and refine it, train it with your style or any other specific artist’s style, and then copy and recreate that style in infinite ways. That has happened to Kelly McKernan, Karla Ortiz, and Sam Yang. The problem is not the tool but how it is used in a way that can have a systematically adverse economic impact on an industry, in this case, the illustrators and visual artists. This tool could be used to copy an existing style of an artist, but it could also help you work 100 times faster in your style. As with most technologies, it’s a double-edged sword but this time can have an enormous impact scale.

So far, the AI industry has been something of a Wild West, with few rules governing the use and development of the technology, not because evil corporations wanted it this way, but simply because this technology was not accessible on consumer technology and, therefore it could not do any harm at scale. However, this is no longer the case, and there is now an urgent need to legislate how nonprofits share databases with for-profit companies. The problem is that the damage is already done because once an algorithm has been trained, the process to untrain it from specific images can be so lengthy that it’s almost better to train a new model from zero. Machine unlearning it’s a new territory of research that hopefully will solve this problem in the future.

Interestingly, we are now seeing platforms like GoFundMe or Kickstarter start to position themselves on this topic, declining some AI projects with troubled copyrights frameworks.

As Alvaro García put it:

You can use any tool to plagiarize anyone but a “tool” that makes this extremely simple and in mass production is not a tool anymore, it is a weapon.

And that is why a fork, which is a tool to eat, is not regulated but a gun is a weapon and has to be regulated.

Some people confuse democratization with degradation and abuse.

THE SIDES

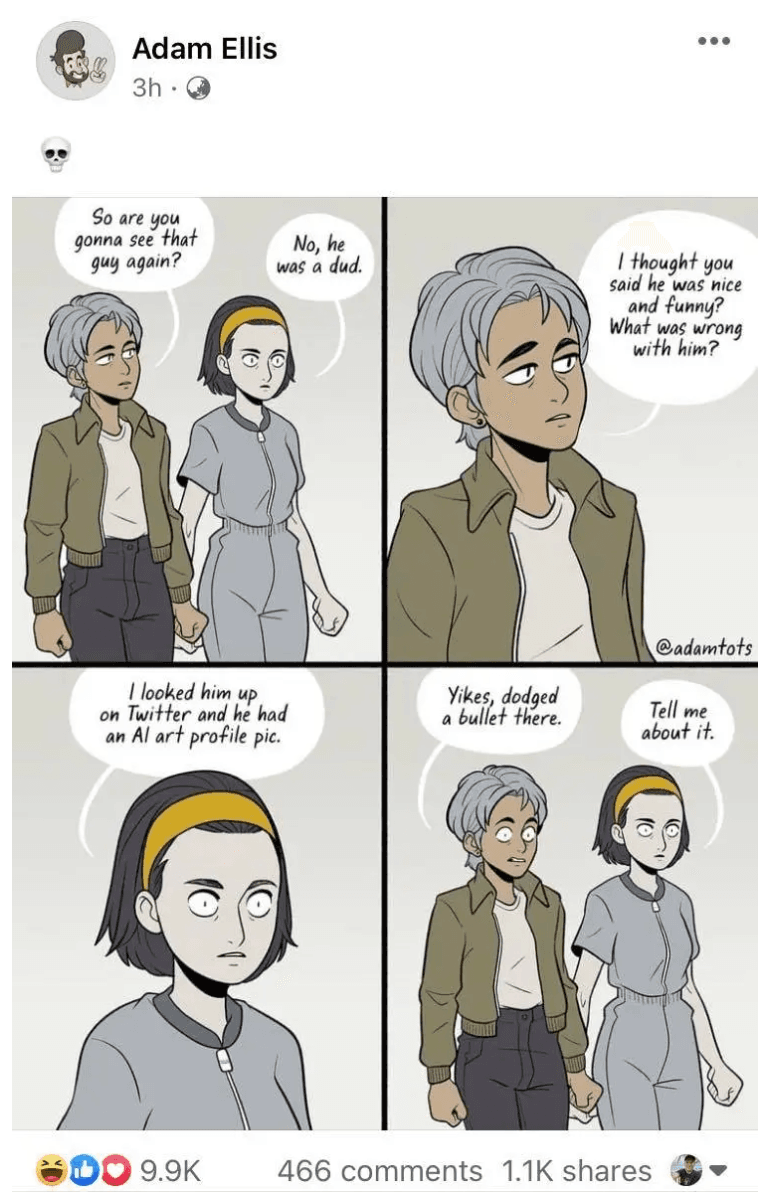

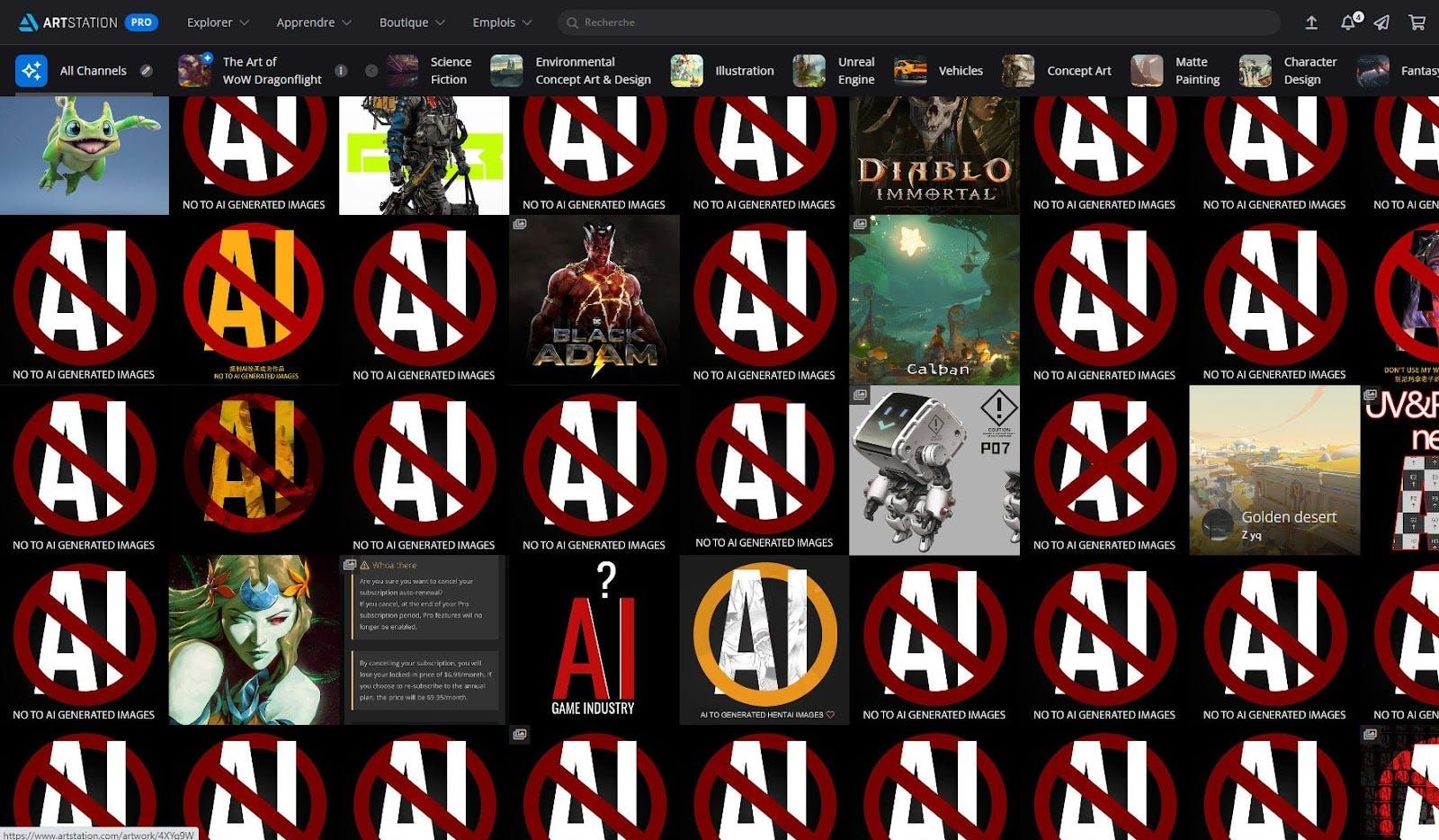

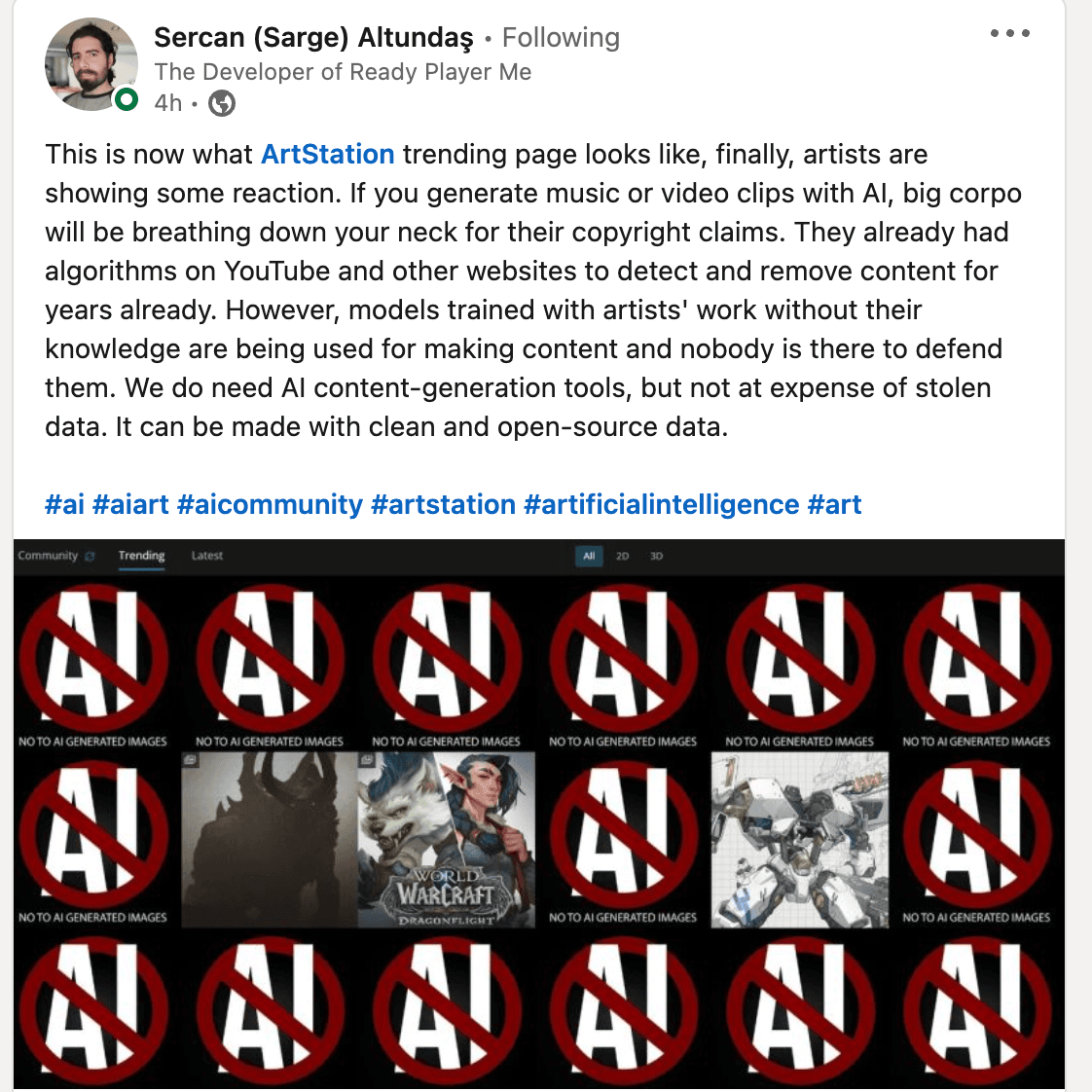

So after the whole scandal of an app making money from the work of hundreds of thousands of artists, we get to the second stage: the beef. ArtStation, a major website that connects gaming, film, media, and entertainment artists, has been at the center of it. The same image has been posted repeatedly by various users on its main page. The image is a giant red “no” sign covering the term “AI,” along with the phrase “NO TO AI GENERATED IMAGES.” Similar things have happened on Instagram and Behance. Obviously, there were dissenting voices with other ideas, but until then, they had been somewhat drowned out.

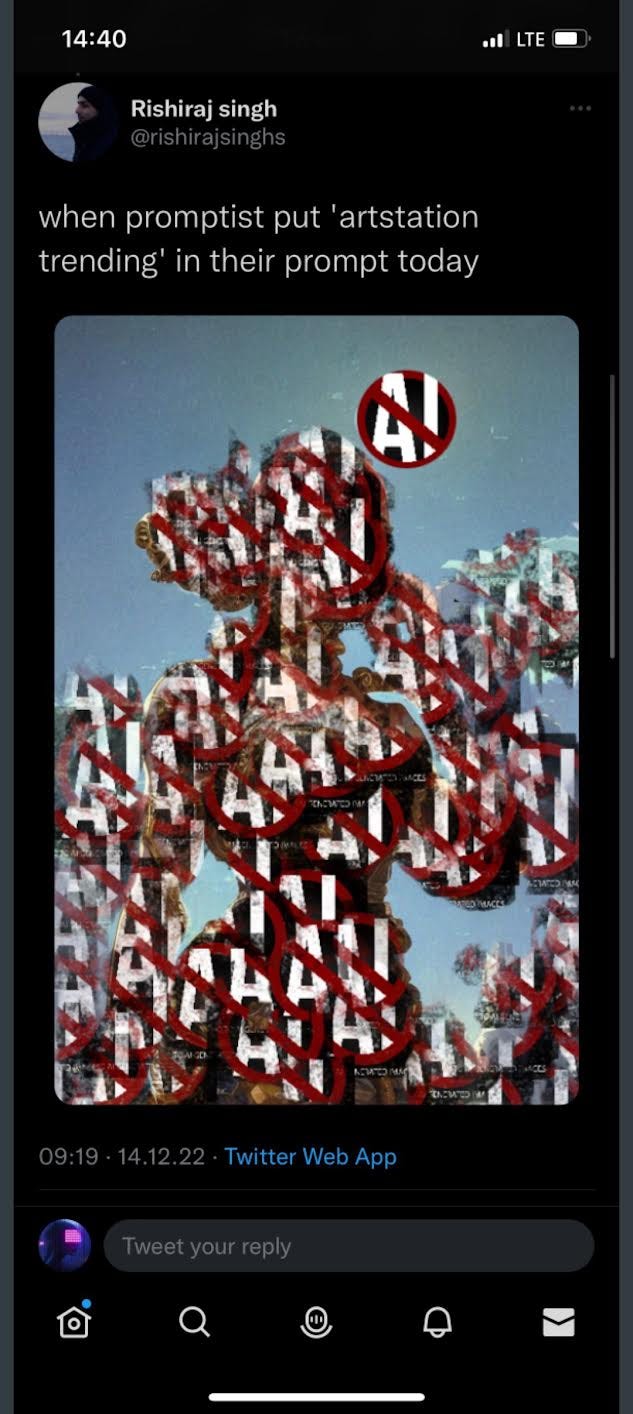

You can see some of the viral tweets below. For a moment, I naively believed that a sudden digital demonstration could impact the software so fast…

The truth is that these images were fakes; you cannot train an image model — especially as big as Midjourney- in under 24h, nor would the flood of anti-ai imagery, consisting of about 0.00000116% of training data, have any meaningful influence. In any case, it helped to trigger more people to position themselves against AI and enter the debate around it.

These ideas make up the majority of the posts that I see on social media, and two relevant figures have dealt very well with some of the most common points: Ryan James Smith in this thread and Nina Geometrieva also did a fantastic job dismantling them in 5 points here:

𝟏 “AI art requires no skill.” This is precisely the same argument used by painters when photography was invented that it’s just about pushing a button. Creating good AI art requires having a taste, envisioning a scene, describing it precisely with words, and then curating and directing it throughout many iterations.

𝟐 “AI steals art.” AI generates brand-new original outputs by default. When AI adds a signature, it simply mimics a common behavior by inventing its own brand-new signature. Artists can of course, specifically direct the AI to create minor variations of existing work, but just like with any tool, one can choose whether to steal or to be original. Blame the artist, not the tool.

𝟑 “AI rehashes art.” No art movement would have existed without people partially leveraging the ideas of others. No memes, no culture. Not even photographers, because they often take photos of other people’s art too (e.g. architecture) and add a new interpretation to it, which doesn’t make it any less of an art.

𝟒 “AI is trained on other people’s art without consent.” From a philosophical perspective, if we accept this argument as valid, then we must also accept that none of us human artists have sought such consent while learning new skills from others either. We all use other people’s art as influence and inspiration, thus “training” our inner algorithm and using that knowledge to create our art. This is no different from how AI works.

𝟓 “AI will steal our jobs.” AI is (just) a fantastic tool. First, there was a brush, and now a prompt. Don’t think of AI as a competitor, but rather as a partner helping you achieve your goals. AI has the power to promote artists to art directors. It is typical for big-shot artists today to hire other artists to help execute their ideas. AI art allows anyone to have this privilege.

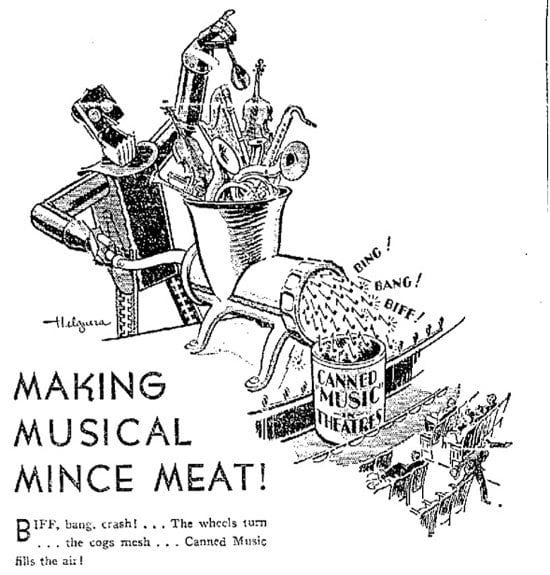

This, again, is a recurrent idea from the industry. In the 1930s, the union of American singers spent the equivalent of about $10M in today’s money on a campaign to stop the mechanization of recorded sound in cinemas instead of live performances. If we look back, we can agree that the introduction of recorded sound in the cinema was a great advancement that left many cinema band musicians behind but ultimately democratized the cinema experience worldwide. It brought sound films to an infinitely wider audience and generated a new industry around sound design and sound engineering.

And the last one is about joy; a lot of the comments I’ve been reading read something like:

If art-making has been the quintessential thing since the beginning of civilization, this is an “unmaking” of ourselves as humans. What will we do for hope, joy, and inspiration when art is no longer an enjoyable hobby or pursuit, when there are no benefits for learning and skill and practice and when art is no longer a difficult challenge?

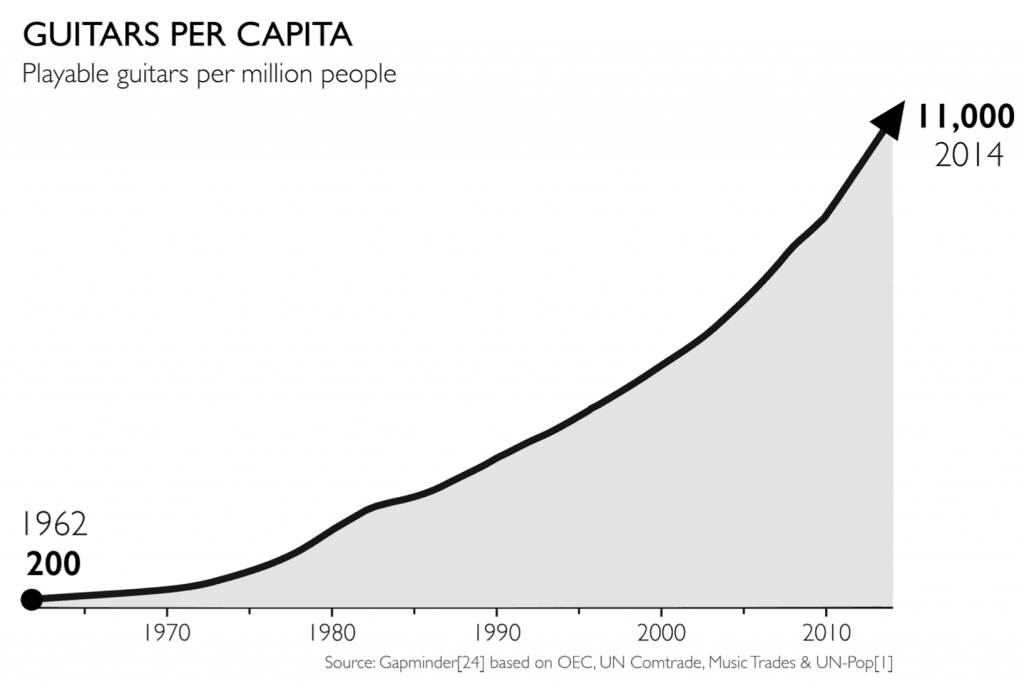

My answer to that is chill. Let’s not get ahead of ourselves. For more than 30 years, the software to create the perfect artificial guitar solo has existed. Yet, the number of guitars per capita in the world has increased dramatically, and millions of people continue to learn to play the guitar daily. Generative AI tools will not dissuade people from learning skills and enjoying themselves through artistic practices. On the contrary, it will most likely stimulate new ways to approach art, popularising new styles and new artistic languages.

WHAT CAN YOU DO AS A CREATOR?

If you are not open to trying AI and being part of this technology, here are some tactics to protect your work:

- Random watermark your work if you want to post it. Don’t repeat patterns, and don’t use the same watermark.

- Add a visual copyright on them ©, and the date and author.

- Hide your art temporally until press/regulation comes in.

- Incorrectly metatag your data in your saved file and the uploaded platforms (Still risky since, in the future, datasets will be manually tagged due to the need for less volume).

In the case that you are interested in using AI as an artist, what I would do is create my own AI model, taking a draft model like Stable Diffusion and training it yourself with your work, then arrange a front-end website where people could use it (free of cost or with a paywall). This way, you will have complete control of what people create using your style, and also define some primary uses and protect the work (for example, you could apply copyright and watermarks over the work).

THE GOOD NEWS

Better late than never, Stable Diffusion announced in December an opt-out program that will remove all work from artists that don’t consent to be part of the database. This is a precedent for other models to follow, and clearly, this will be transformed into an opt-in program in the future, replacing the previous assumption that everyone is okay with these models using their work unless they offer direct opposition. This should and will change.

Lately, I’ve been following this GoFundMe campaign that, as of today, has already achieved 200.000$ in the fund to lobby in Washington D.C. to “protect the artist from AI Technologies.” Their main requests are the following:

- Ensure that all AI/ML models that specialize in visual works, audio works, film works, likenesses, etc., utilize public domain content or legally purchased photo stock sets. This could potentially mean current companies shift, even destroy their current models, to the public domain.

- Urgently remove all artists’ work from data sets and latent spaces via algorithmic disgorgement. Immediately shift plans to public domain models, so Opt-in becomes the standard.

- Opt-in programs for artists to offer payment (upfront sums and royalties) every time an artist’s work is utilized for a generation, including training data, deep learning, the final image, the final product, etc. AI companies offer true removal of their data within AI/ML models just in case licensing contracts are breached.

- AI Companies pay all affected artists a sum per generation. This is to compensate/back pay artists for utilizing their works and names without permission for as long as the company has been for profit.

And this is just a starting point. In 2023 things are going to change from a regulatory standpoint. We will see the final version of the AI law in the EU (The AI Act) passed and potentially applied as early as the summer. It will include bans on any AI practices against human rights, such as the systems that score and rank people’s trustworthiness (insurance companies, banks, flight companies). Also, it will become mandatory to indicate when people are interacting with deep fakes or AI-generated images, audio, or video.

The use of facial recognition technology in public places will also be restricted by law in Europe, and there’s even momentum to prohibit law enforcement from using them entirely. The EU is also working on a new law to hold 3rd party companies accountable for using this software in ways that contribute to privacy infringement or unfair algorithm decisions.

In the United States, the Federal Trade Commission forced weight loss company Weight Watchers to destroy data and algorithms because it had collected data on children illegally. In late December, Epic, which makes games like Fortnite, had to pay a $520 million settlement for the same reason. This is just a precedent of what is to come within the following year.

As of the 10th of January, China will be the first country to ban deep fakes without the subject’s consent.

All these regulations will shape both how technology is built in the future and how it affects our society, and their challenge will be to ensure the laws are precise enough to be successful and protect people, but not so particular that they soon become outdated.

I’m sure that Pablo Picasso’s quote, “Good artists copy, great artists steal” could never have been more pertinent nor antagonistic than it is today. Let’s not forget that AI generative tools are only possible because of the massive datasets formed of human-created art and text used to train them. While using these tools to create and distribute art may be legal, it’s important to consider the impact on the creators whose work is being used and potentially exploited by corporations and companies.

Let’s have a responsible conversation about compensating and supporting these artists fairly. Let’s build an AI environment that we can be proud of.

I just wanted to take a moment to express my gratitude to the Reddit community for all the helpful feedback and suggestions provided on my article. Special shoutout to user mxby7e — your constructive criticism and detailed suggestions were especially appreciated. Thank you for taking the time to help me out; it truly made a difference.