In September 2022, there was an outcry of despair across social networks heralding the imminent demise of art at the hands of generative AI. Artists were rightly pointing out the opaque and ethically dubious training of these AI models and how easy this was making it to steal not only their work, but also their way of making a living from art. On the opposite side, the AI enthusiasts were jumping to defend these technologies, with some labelling the critics as Luddites.

It was during this tumultuous period that I first encountered the term “Luddite” being thrown around. AI skeptics who voiced criticisms and concerns were swiftly labeled as “Luddites” for the opinions they shared. This term, which we had only briefly touched on during my school days, began to pique my interest and I decided to delve a little deeper into its origins.

It turns out that Luddism is not simply a rejection of recent technology, but a movement dating back to the English textile workers of the early 19th century. These workers, known as Luddites, were not against technology per se. Their main grievances were the plummeting wages, the rising profits of the factory owners, and the escalating food prices. They rallied against the inhumane working conditions, the exploitation of child labour, and the production of subpar goods that tarnished the reputation of the entire textile industry. Contrary to popular belief, Luddites did not want just to destroy machinery at random, but targeted those machines owned by employers who underpaid their workers. Their acts of machine-breaking were desperate cries for economic fairness and justice.

It’s intriguing how the use of the term “Luddite” has evolved over time. Today, it’s often used derogatorily, implying that someone is irrationally resistant to new technology. This modern interpretation is a clear misunderstanding of the original Luddite movement, which was more about economic justice than a blanket rejection of technology.

This summer, I received a present from my former professor Ariel Guerzenvaig that would lead me to further explore the contemporary relevance of this movement; a very short paperback book called Ned Lud & Queen Mab, Machine-Breaking, Romanticism and the Several Commons of 1811–12. Here, I share my favourite insights:

A legendary origin:

The Luddites found inspiration in the legendary figure of Ned Ludd, who in 1779 was said to have broken two stocking frames in a fit of rage. When the “Luddites” emerged in the 1810s, his identity was appropriated to become the folkloric character of Captain Ludd, also known as King Lud or General Ludd, the Luddites’ alleged leader and founder. This story can be traced to an article in The Nottingham Review on 20 December 1811, but there is no independent evidence of its veracity.

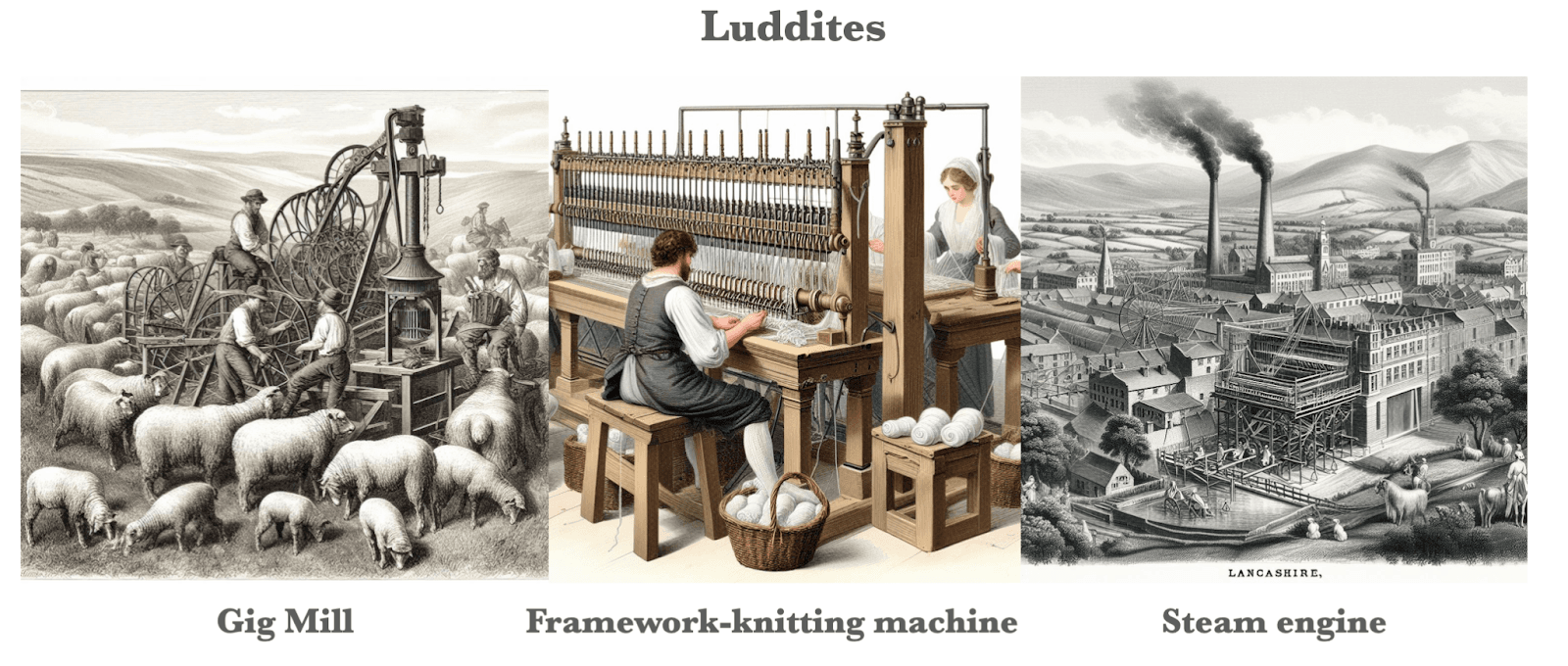

The triangle of resistance: The Luddites focussed their fight on three regions of England, each one being simultaneously hit by a new invention that was transforming the textile industry:

- In the West Riding of Yorkshirecroppers were threatened by the gig mill or shearing machine.

- In Nottinghamshire, the stockingers were being made redundant by the framework-knitting machine.

- In Lancashire, the cotton weavers were losing work because of the application of the steam engine to the hand-loom.

This area of England was known as the Luddite Triangle, and it was where the majority of Luddite resistance took place in the early 19th century. Three revolutionary machines invoking rapid transformation of the labour market is a scenario that feels particularly familiar and relevant today. I see how the community of illustrators is being impacted by image generation tools, while screenwriters are contending with ChatGPT, and actors consider the implications of deep fake technology (as we saw in the Black Mirror’s Joan is Awful episode)

The alienation problem: With the emergence of heavy machinery and automated production methods, artisan workshops specialised in one craft were rapidly replaced with factories, rendering many specialised skills worthless and their practitioners easily replaceable. This scenario was anticipated in Adam Smith’s Wealth of Nations: “In the progress of the division of labour, the employment… of the great body of the people, comes to be confined to a few very simple operations, frequently to one or two. The man whose whole life is spent in performing a few simple operations… generally becomes as stupid and ignorant as it is possible for a human creature to become” (Book V, chapter 1 in Adam Smith, The Wealth of Nations (1776), ed. Edwin Seligman, two vols. (London: Dent, 1958), ii,264.)

With this division of labour, the means of production are taken from the artisans and placed into the hands of those with the economic power to invest in manufacturing machines. Knowledge and experience, in that sense, become secondary to the speed of production. Somehow, it makes us think that the capacity of production and reproduction will always build an unbalanced power between the community of producers and the ones that are capable of replacing them.

English Luddites were not alone: Americans rose up too, but not without struggle; Luddites, in this case, were rebelling slaves. The destruction of farm implements and tools by those working them on American plantations belongs to the story of Luddism, not just because they, too, were tool-breakers, but because they were part of the Atlantic recomposition of textile labour power. They grew the cotton that was spun and woven in Lancashire. The story of the plantation slaves has been separated from the story of the Luddites, mainly due to the distinctions of wage and slave labour or because of artificial, national, or racial differences.

A South Carolina planter wrote in 1855: “The Nigger Hoe,” often found in relatively advanced Virginia, weighed much more than the “Yankees Hoe,” which slaves broke easily. Those used in the Southwest weighed almost three times as much as those manufactured in the North.

A Louisiana editor wrote in 1849, “They break and destroy more farming utensils, ruin more carts, break more gates, spoil more cattle and hostess and commit more waste than five times the number of white laborers do” (Eugene D. Genovese, The Political Economy of Slavery: Studies in the Economy & Society of the Slave South(New York: Vintage , 1967), 55; Roll, Jordan, Roll: The world the salves made (New York: Pantheon, 1974),300.)

The hidden debate: There is a big abstraction around Luddism, words such as “capital,” “progress” and “property”. What do we mean when we say “technology” or “law”? There is violence in the abstraction of certain words as they hide the real negotiation between who owns the tools, who makes them work, and who profits from them. In the end, these machines used cotton or wool that was grown on plantations and the other raised in pastures. Who covered themselves with these clothes, and who made money from it? These are the real questions of use-value we should be doing and understanding if it’s right or wrong to break a machine when the system that represents it is entirely wrong.

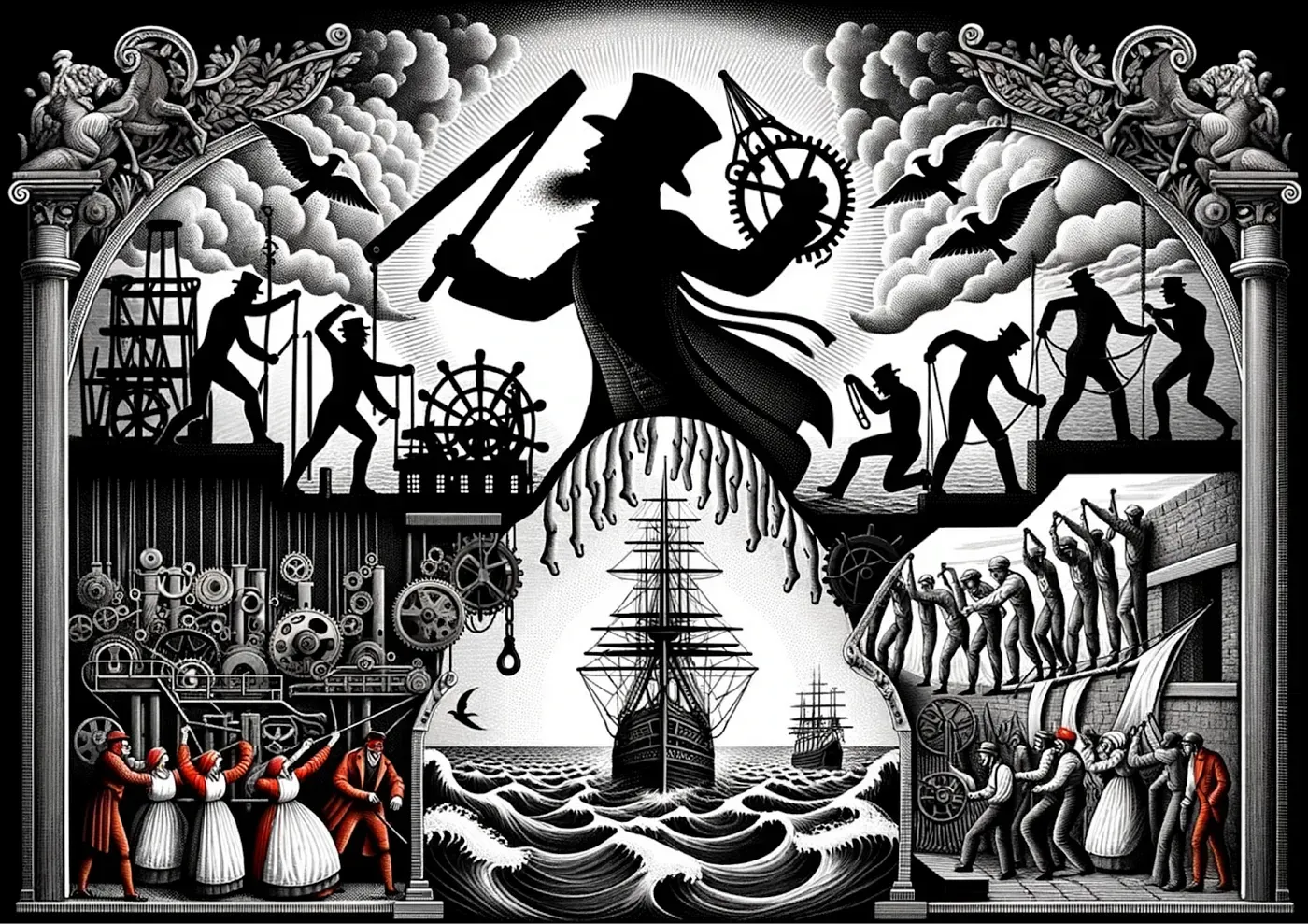

Consequences: The radical acts of protest by the Luddites were not without a reaction. Investment of constant capital in dockside infrastructure, colossal building projects accomplished in the first decade of the century which quickly destroyed the docker’s neighborhoods, and created titanic enclosure walls, locks, and canals around the commercial fortress. It was the beginning of the militarization of commercial space in Europe.

War and machines: From the steam engine to nuclear power, most of the breakthroughs in industrial technology during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries came about as a result of wartime innovation. Whilst these technologies eventually brought progress, improvement, and development, they were also used to bring hell on earth. Up until now, Artificial Intelligence has followed a similar path of research and application that we see in technologies that have been used as weapons and tools of war and oppression.

The misleading truth: The permanence of capitalism seems to rest on the inevitability of technological progress. Luddites opposed that inevitability. I feel today, we have something similar with GEN-AI opponents. The question again is not if you are an opponent of AI but an opponent of an unequal system that protects the interest of the few in the name of progress and, in this case, synthesised in a GEN-AI system.

This is an opportunity to reflect on which framework we use to develop technologies such as GEN-AI. Are these always developed in the framework of optimisation and efficiency that only seeks to increase market value? We might discover a huge expanse of further potential for these tools if we start to think of them within other frameworks, such as care or human rights. Maybe we should question why the word Luddite continues to resurface and who is defining it as inherently bad.

When someone is accused of being a luddite, it’s worth asking, is this person actually against technology? Or are they in favour of economic justice? Furthermore, is the person accusing them actually in favour of improving people’s lives? Or are they just trying to increase the individual accumulation of capital?

References

- Hammond, J. L.; Hammond, Barbara (1919). The Skilled Labourer 1760–1832. London: Longmans, Green, and Co. p. 259.

- Chase, Alston (2001). In a Dark Wood. Transaction Publishers. p. 41. ISBN 978–0–7658–0752–6.

- Alsen, Eberhard (2000). New Romanticism: American Fiction. Routledge. p. 43. ISBN 978–0–8153–3548–1.

- Byron, George Gordon (2002). The Works of Lord Byron. Letters and Journals. Adamant Media Corporation. p. 97. ISBN 978–1–4021–7225–0.